Part 6: Utilising flexible enforcement and Antitrust Guidelines for Standard Essential Patents

1. SAMR’s growing use of soft enforcement to support routine oversight

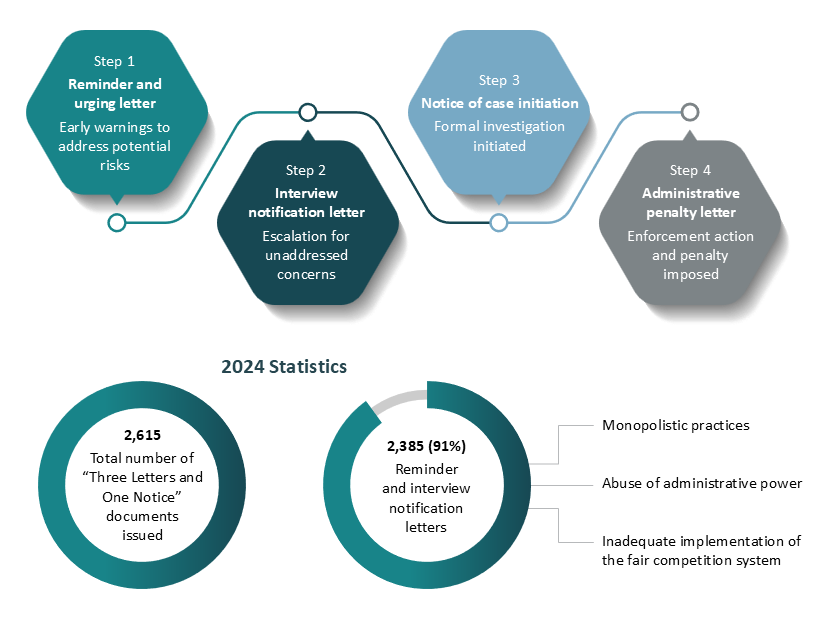

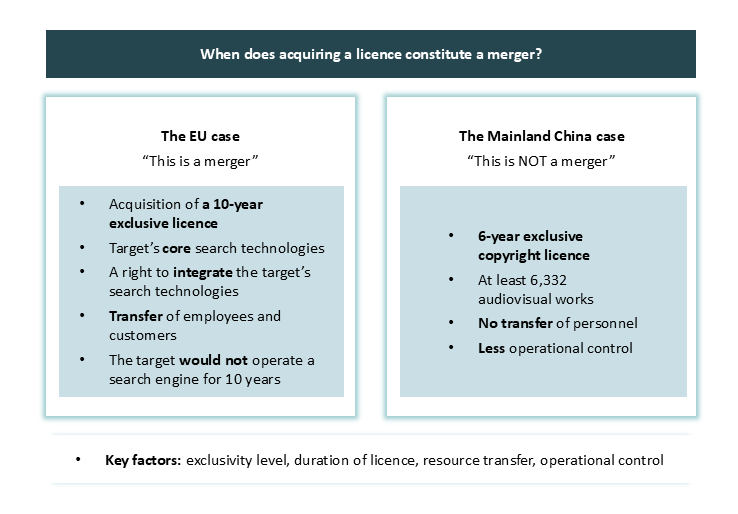

Since its launch in December 2023, the “Three Letters and One Notice” scheme has become a key tool in proactive supervision of the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR). This initiative is a key component of its oversight activities.

Figure 1: “Three Letters and One Notice” scheme

Sources: Official scheme introduction and 2024 statistics

SAMR’s “Three Letters and One Notice” scheme is designed to flag risk early and avoid lengthy formal investigations. Companies receiving such letters should respond promptly and proactively manage compliance risks.

1.1 Application in the automotive sector

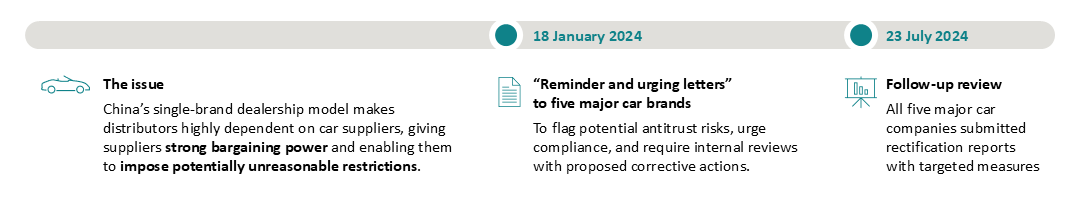

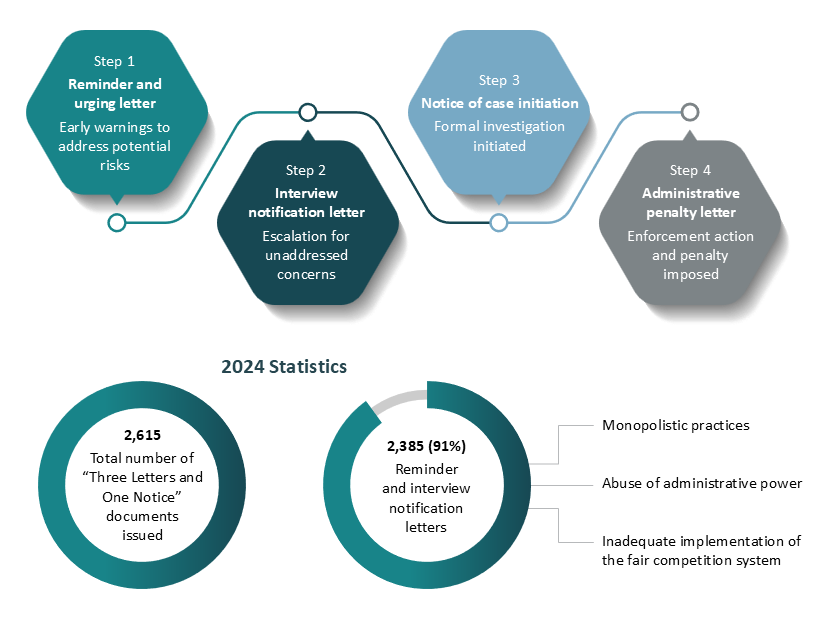

On 18 January 2024, five major car brands received SAMR’s reminder and urging letters, reportedly over distribution restrictions stemming from their bargaining power under the country’s prevalent single-brand dealership model. SAMR urged them to strengthen compliance, conduct self-assessments and implement corrective measures.

This highlights SAMR’s focus on car distribution, where unequal market power can lead to vertical restraints such as resale price maintenance (RPM), procurement quotas, inventory rules and bundling. This follows past fines against car suppliers for RPM restrictions.

Figure 2: Reminder and urging letters to major car brands

Source: SAMR report

1.2 Letters to Avanci – a patent pool

On 27 June 2024, SAMR issued a reminder and urging letter to Avanci, raising concerns over its licence practices for standard essential patent (SEP) in automotive wireless communications. The letter urged compliance risk assessment and corrective actions.

Avanci pools SEPs from multiple holders into a single licensing platform. It bundles complementary and interchangeable SEPs across different production lines, giving it significant bargaining power. Key concerns include:

- Excessive pricing for access to essential technology

- Lack of transparency in fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (“FRAND”) terms

- Bundling non-essential patents with essential ones

- Restricting SEP holders from joining competing patent pools

Avanci responded to SAMR promptly, claiming full compliance with antitrust rules both domestically and globally.

2. Antitrust guidelines for SEPs (the “Guidelines”)

The Guidelines come at a crucial time as emerging technologies such as IoT, 5G, AI, cloud computing, data analytics and autonomous vehicles create increasingly complex innovation landscapes. Building upon earlier IP sector guidelines, they underscore balancing IP protection with fair competition and the interests of both SEP holders and licensees.

The Guidelines exhibit certain highlights:

2.1 Enhanced ex-ante regulation

The Guidelines stress the importance of ex-ante regulation, encouraging entities to report potential anti-competitive risks during critical phases such as standard setting and implementation, patent pool management and the licensing of SEPs. Regulators may issue reminders and urging letters to prompt early corrections.

Section 2 outlines “good practices” to foster compliance and transparency. These include sufficient disclosure during standard setting, adherence to the FRAND terms, and clear rules for good faith SEP licensing negotiations.

While not mandatory, failure to follow these “good practices” may raise antitrust risk under the Anti-Monopoly Law (AML).

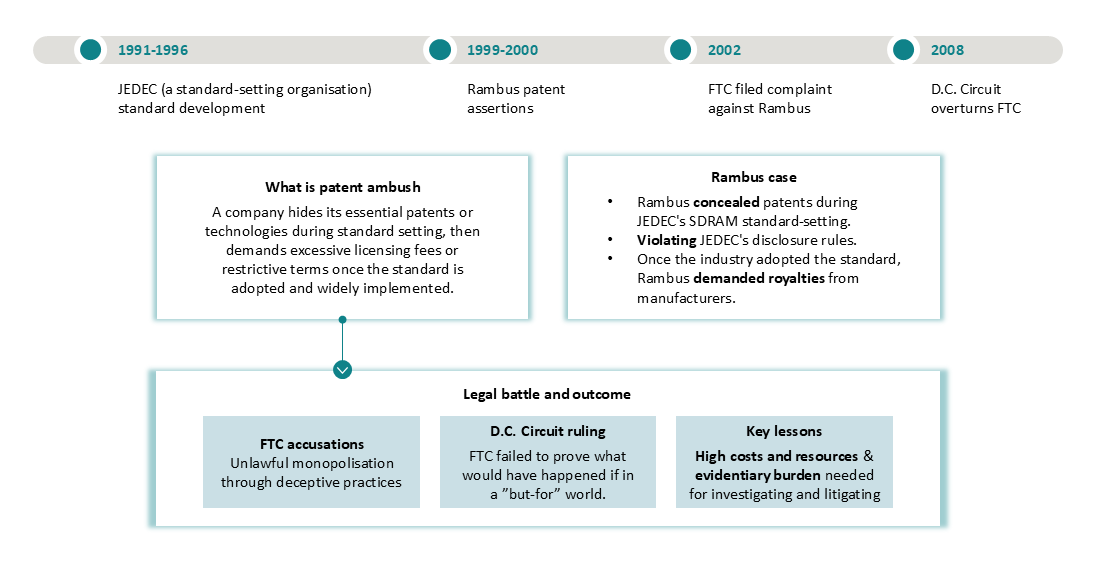

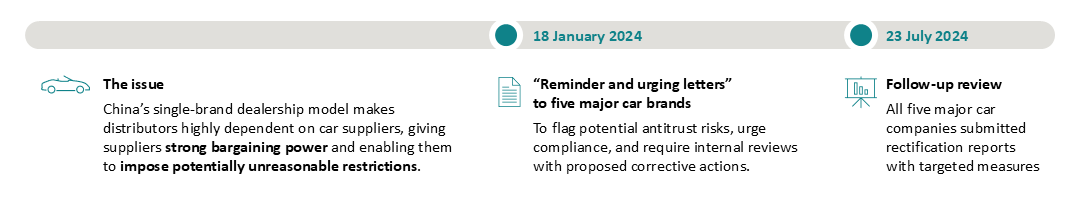

Figure 3: Rambus patent ambush case

The Rambus case is a key example of how bad-faith conduct – such as a “patent ambush” during standard setting – can amount to an antitrust violation.

Source: FTC report

2.2 SEP-related potential monopoly agreements

Articles 9 to 11 of the Guidelines outline circumstances where SEP-related agreements – whether during SEP setting in the formation of patent pools, or through contractual restrictions on implementers – may raise antitrust concerns.

These provisions warn standard-setting organisations (SSOs) and their members to avoid:

- Abuse during standard-setting and implementation: boycotting competitors or excluding competing technologies.

- Patent pools risks: exchange of sensitive information, excluding competing patents, or limiting individual licensing outside the pool.

- Implementing restrictions: setting limits on price, quality, quantity and geographic scope, or alternative technology development.

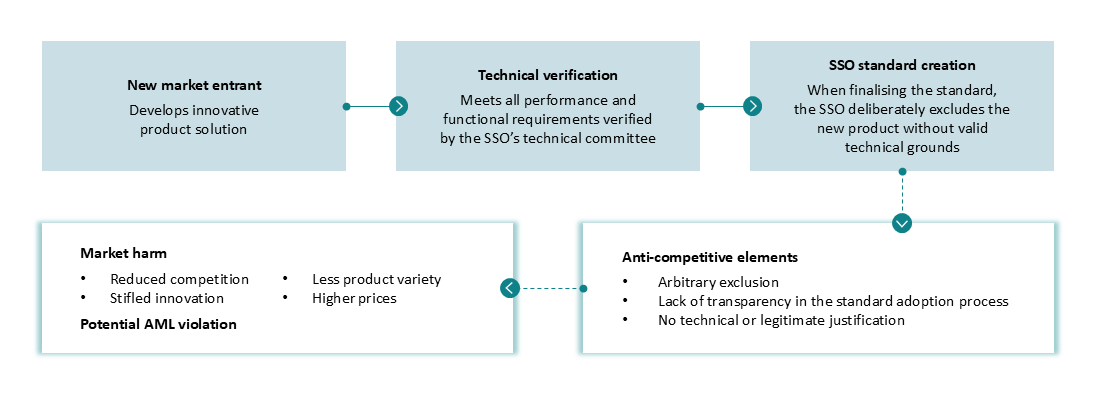

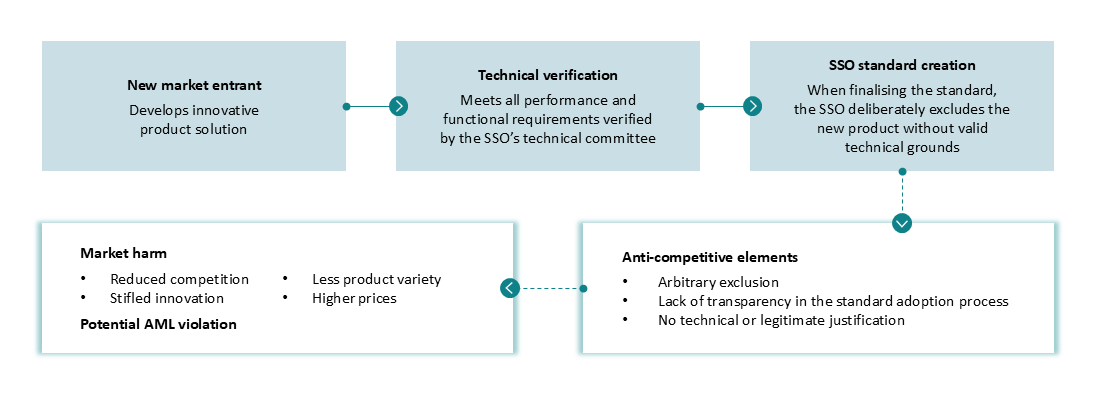

Figure 4: Hypothetical example – restrictive standard-setting process

This example illustrates how SSOs may engage in anticompetitive conduct through manipulative standard-setting processes.

2.3 Potential abusive conduct related to SEPs

Abuse of market dominance is a key concern in the SEP sector. The Guidelines outline six types of potentially abusive conduct by SEP holders, while also recognising possible justifications.

These include: (1) excessive pricing, (2) refusal to license, (3) forced package licensing or bundling SEPs with non-SEPs, (4) imposing unreasonable trading conditions, (5) discriminatory treatment, and (6) abuse of remedial measures.

(1) Excessive pricing

Without adherence to FRAND commitments, SEP holders may gain disproportionate bargaining power over licensees. The Guidelines provide factors for assessing excessive pricing, including:

- Comparisons with historical licensing fees or fees charged by other SEP holders

- Inclusion of expired, invalid or non-essential patents in the licensing package

- Whether fees reflect changes in the number, quality or value of the SEPs

- Risks of duplicate charges for the same SEPs

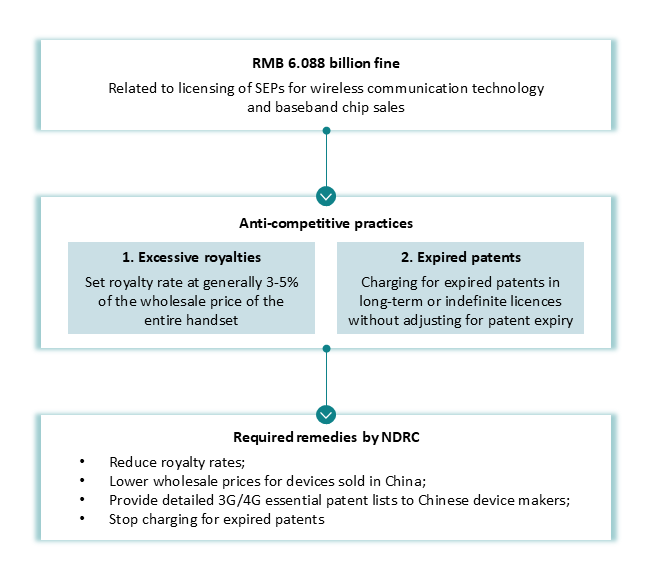

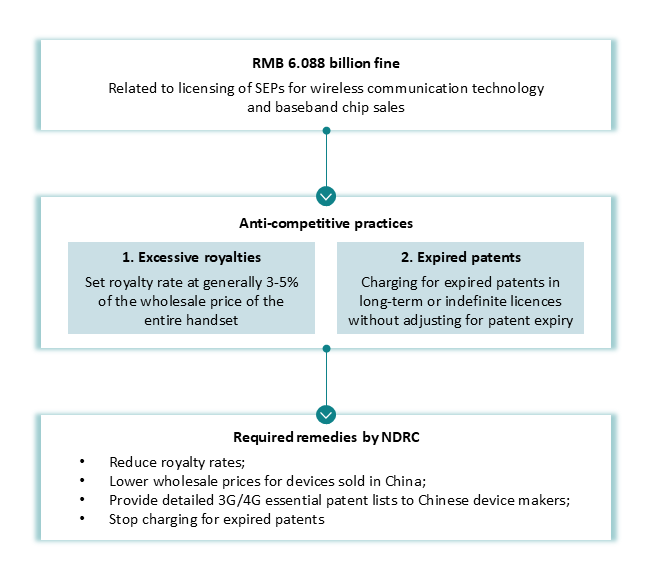

Figure 5: Qualcomm case (by National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC, the former antitrust authority)

The Qualcomm case is a key example of excessive pricing:

Source: Compiled from the Qualcomm case

(2) Refusal to license

A dominant SEP holder’s refusal to license may be abusive, particularly when the patent is indispensable for making standard-compliant products. SEP holders are generally expected to offer licences under the AML.

However, refusal may be justified if the licensee shows no genuine willingness to negotiate on FRAND terms – a form of “hold-up” in the SEP context. Burden is shifted when there are delays or tactics to pressure SEP holders into offering more favourable terms, or to force litigation for securing a court-determined FRAND rate instead of negotiating one.

The Guidelines consider factors to assess such refusals, including adherence to good practices, material changes affecting implementers, force majeure and overall market impact.

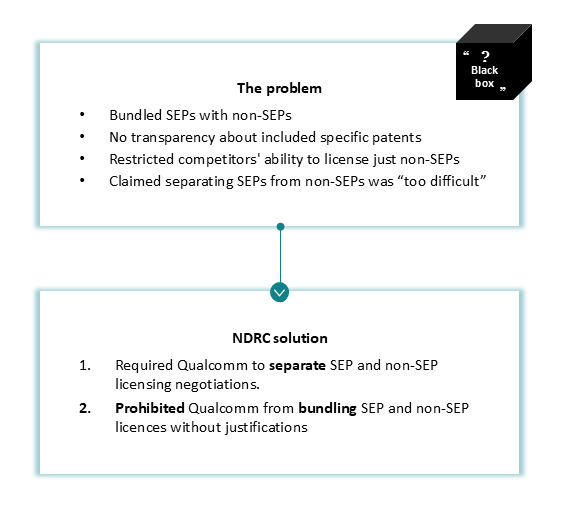

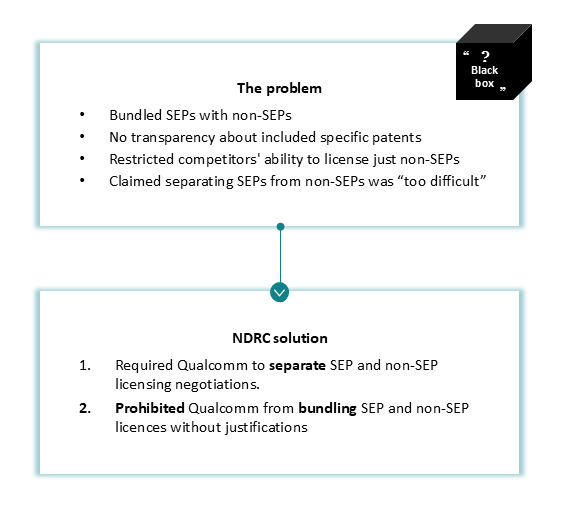

(3) Bundling practice related to SEP licensing

SEP holders may bundle essential and non-essential patents in licensing offers. The Guidelines assess such practices based on factors like compliance with good practices, industry norms, technical necessities, feasibility of separating the bundle, potential implementation costs and whether implementers have options to choose specific licences.

Figure 6: Qualcomm case

Source: Compiled from the Qualcomm case

(4) Unreasonable licensing terms

The Guidelines warn SEP holders against using their bargaining power to impose unfair terms.

Problematic practices include: requiring free or unfair reverse licence, forcing uncompensated cross-licences, limiting SEP challenges, restricting dispute resolution options, interfering with third party transactions, preventing competing technologies and demanding irrelevant disclosures.

In the Qualcomm case, the NDRC found such abuses including:

- uncompensated cross-licence demands for certain non-SEPs, and

- restrictions on patent challenges against Qualcomm or its licensees.

Qualcomm later agreed to good-faith negotiations with Mainland China firms under a rectification plan.

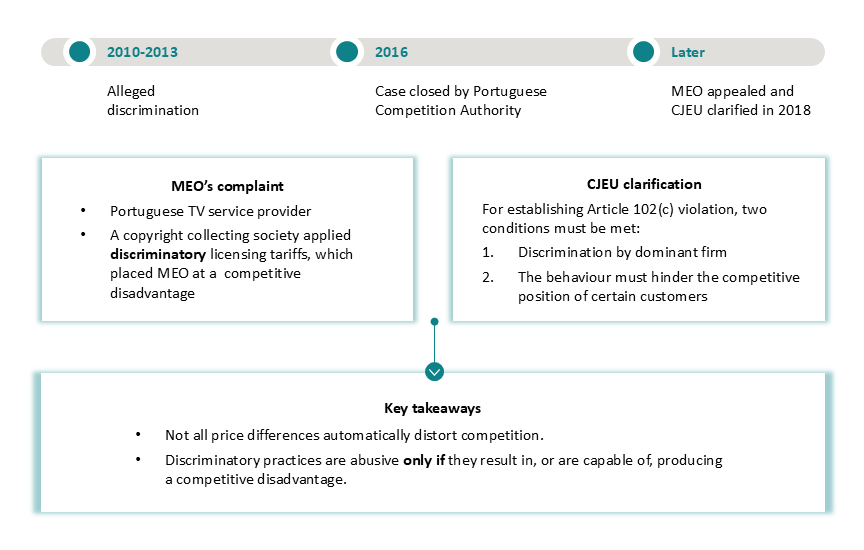

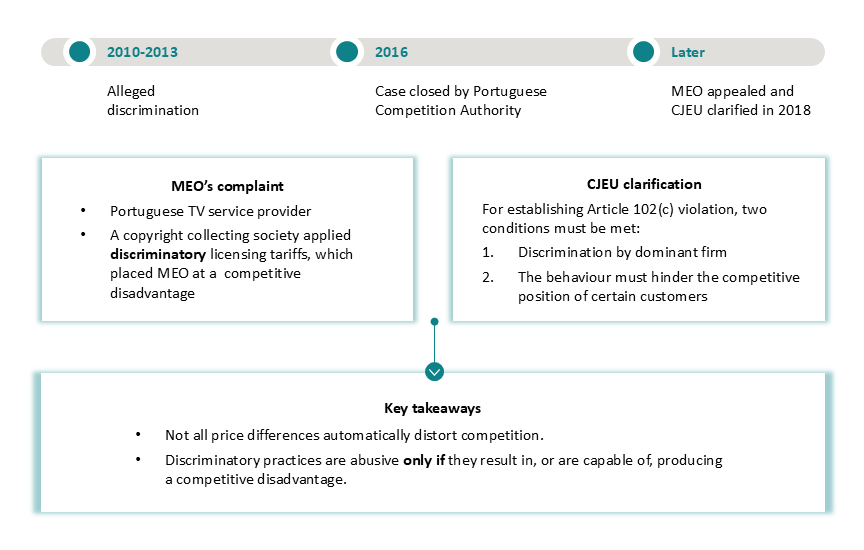

(5) Discriminatory treatment on implementers of similar conditions

Non-discriminatory licensing is central to FRAND commitment. While some variation in SEP terms is allowed based on objective factors, unjustified differences in treating implementers under similar conditions may be anti-competitive.

The Guidelines consider factors such as adherence to good practices, market timing, comparability of implementers and terms, other agreed conditions, and competitive impact.

Figure 7: MEO case

Source: Compiled from the MEO case

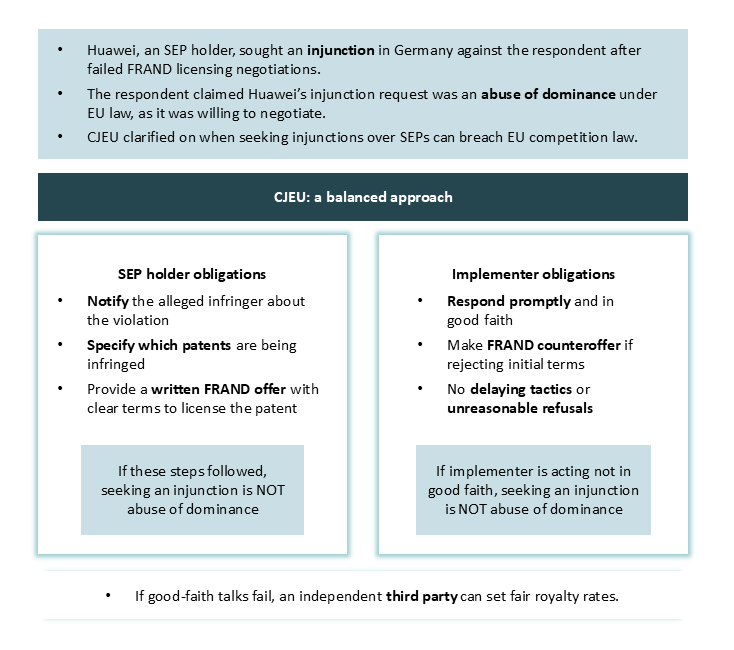

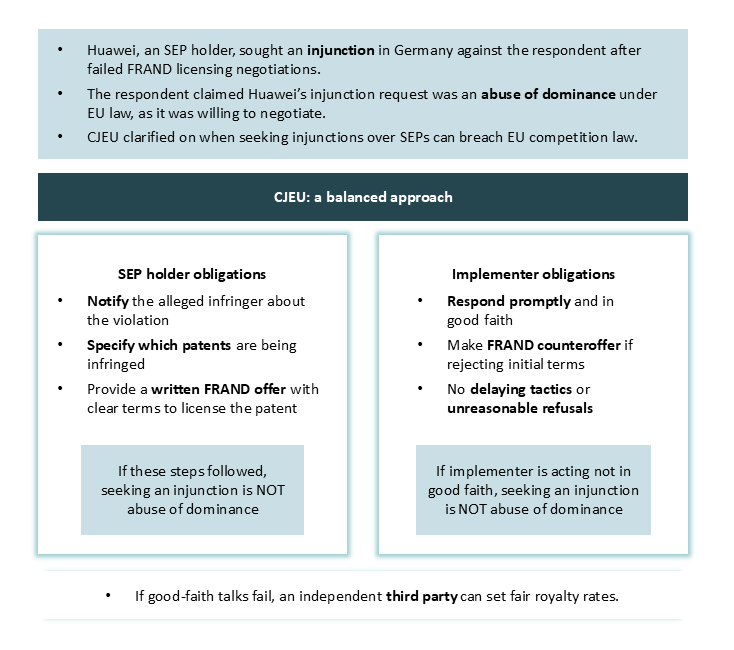

(6) Abuse of remedial measures

The Guidelines warn that misusing injunctions in SEP disputes can restrict competition. While SEP holders may seek injunctions over FRAND disputes, doing so unfairly – especially when the licensee is willing to negotiate – may constitute an abuse of dominance.

Though the Guidelines do not define clear thresholds, the Huawei case provides insight into this issue.

Figure 8: Huawei case

Source: Compiled from the Huawei case

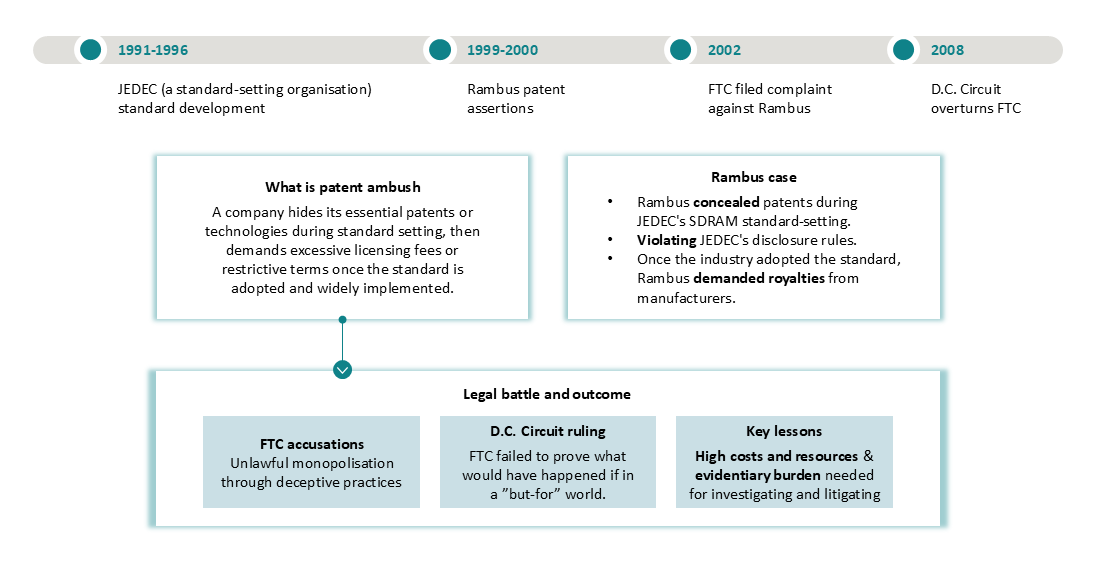

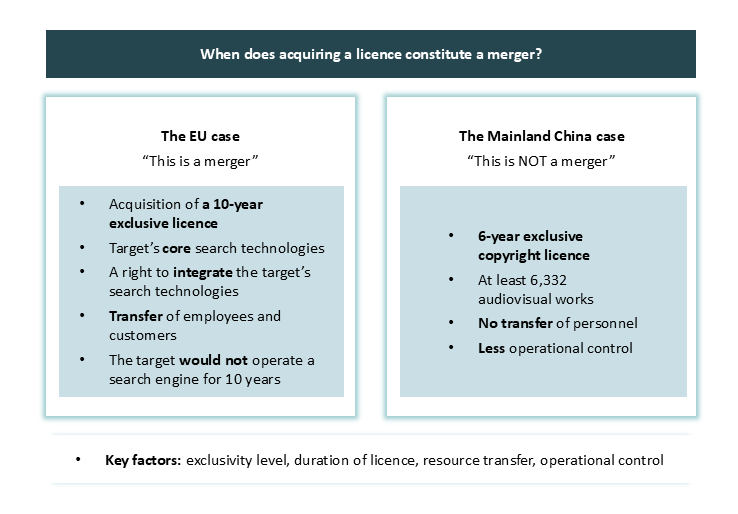

2.4 Merger control and SEPs

SEP transactions may trigger merger control. The Guidelines focus on whether SEP-based products or services form an independent, revenue-generating business, and consider licensing methods and duration. Though the criteria are not detailed, acquiring SEPs may confer lasting control and thus likely require merger review.

Figure 9: Similar cases with different outcomes

EU Microsoft’s search business licence deal v Mainland China Huaxiu licence deal

3. Closing remarks

From 2024 through Q1 2025, SAMR has intensified its enforcement efforts, aligning more closely with global norms while expanding into both traditional and emerging sectors. This trend is expected to continue, with more investigations, refined guidance and increased focus on sensitive and high-stakes industries.

In this evolving landscape, staying ahead is vital. Companies should strengthen antitrust compliance, integrate regulatory risks early in deal planning and closely monitor policy changes. Proactive engagement and preparedness are key to managing challenges and seizing opportunities in Mainland China’s dynamic regulatory environment.

Stay tuned for our ongoing insights on competition enforcement and risk management across Greater China.