Part 5: Key developments in abuse of dominance enforcement

1. Overview of abuse of market dominance cases

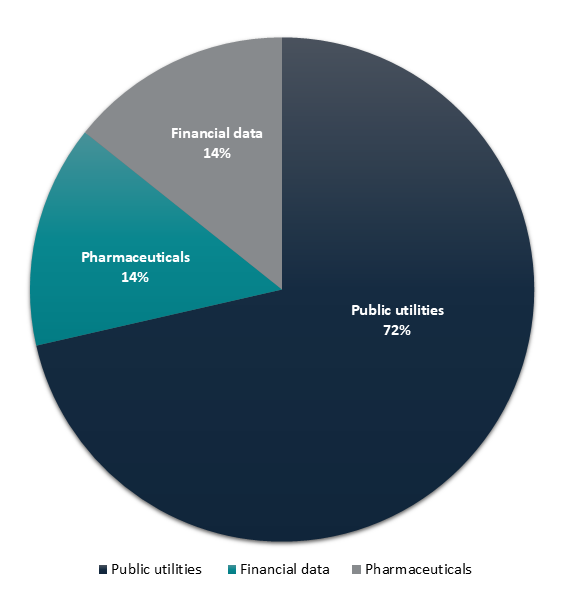

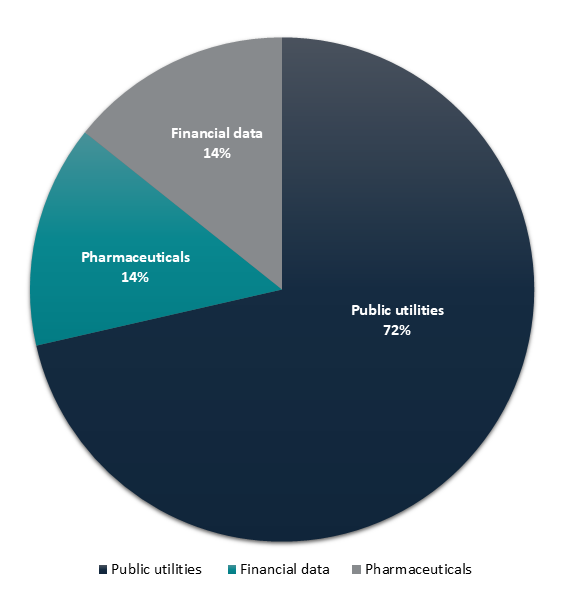

From 2024 to Q1 2025, seven abuse of market dominance cases were penalised.

Figure 1: Sector distribution of abuse of dominance cases (2024 – Q1 2025)

Source: State Administration for Market Regulation (“SAMR”)’s website

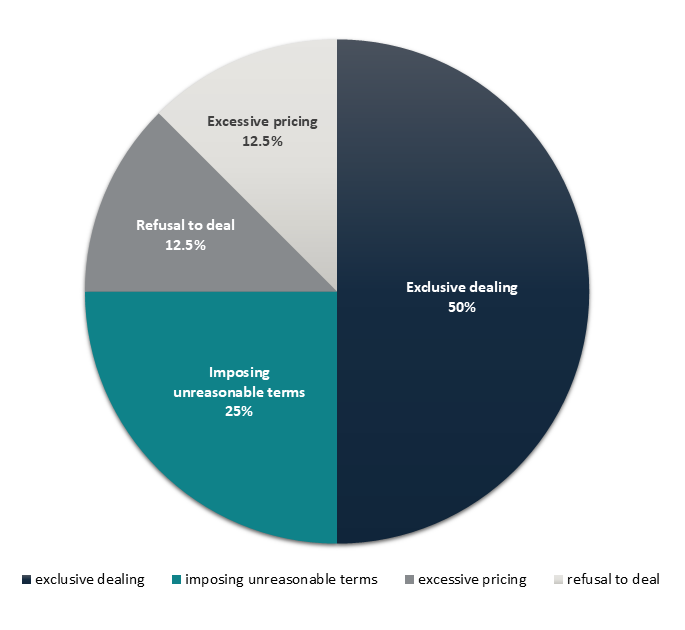

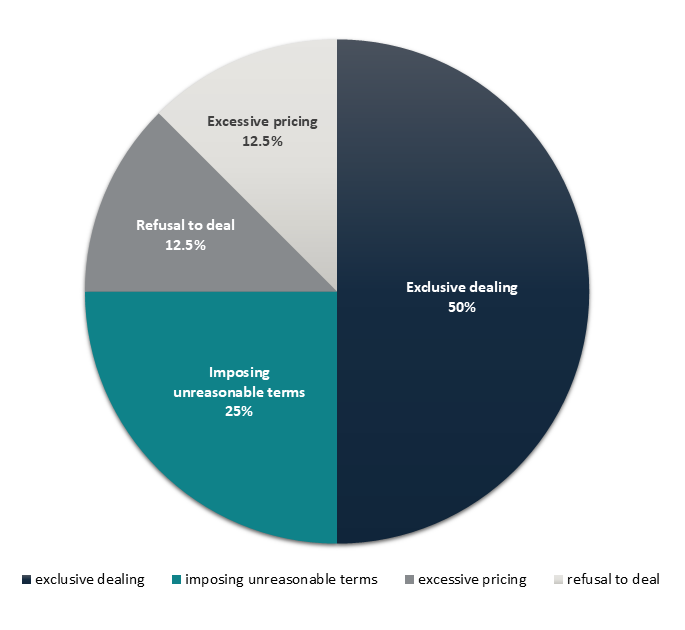

Figure 2: Distribution of conduct in these seven cases

Source: SAMR’s website

1.1 Key takeaways from abuse of dominance cases during this period:

- Penalties: Total fines reached around RMB 88.4 million, often combining confiscation of illegal gains with turnover-based fines. This approach is more practical in abuse of dominance than cartel cases, since the former involve clear markets and focus on one company’s records.

Where illegal gains are not confiscated, higher turnover-based fines (e.g. Jiangxi Pharma Case) are typically imposed to ensure adequate deterrence, unless mitigating reduction factors are applied (e.g. Sumscope Case).

- Sectors under close scrutiny:

- Public utilities: Due to their quasi-monopoly status, public utilities remain a key focus – a risk addressed under Article 23 of the Provisions on Prohibiting Abuse of Market Dominance. In the Shandong Water Utilities Case, the regulator stressed that these providers have a greater responsibility to prevent anti-competitive practices, including informing customers of alternative service providers. Failure to do so can potentially lead to customer foreclosure.

- Pharmaceutical sector: Remains highly susceptible to market dominance abuse, given high entry barriers including regulation, R&D investment and technological complexity.

- Financial data: 2024 marked the first antitrust case in the emerging data-intensive sector (details below).

- Common abuses: Exclusive dealing – forcing customers to buy related services exclusively – was the most common form during the period, particularly in public utilities. This effectively extends dominance from core services into complementary services, highlighting a key antitrust concern.

Excessive pricing remains a recurring issue that continues to draw regulatory attention in pharma cases.

2. First case in financial data sector – Sumscope

Ningbo SUMSCOPE Information Technology’s abuse case (“Sumscope Case”) stands out as a milestone in Mainland China, as well as globally, signalling growing focus on data-intensive emerging markets.

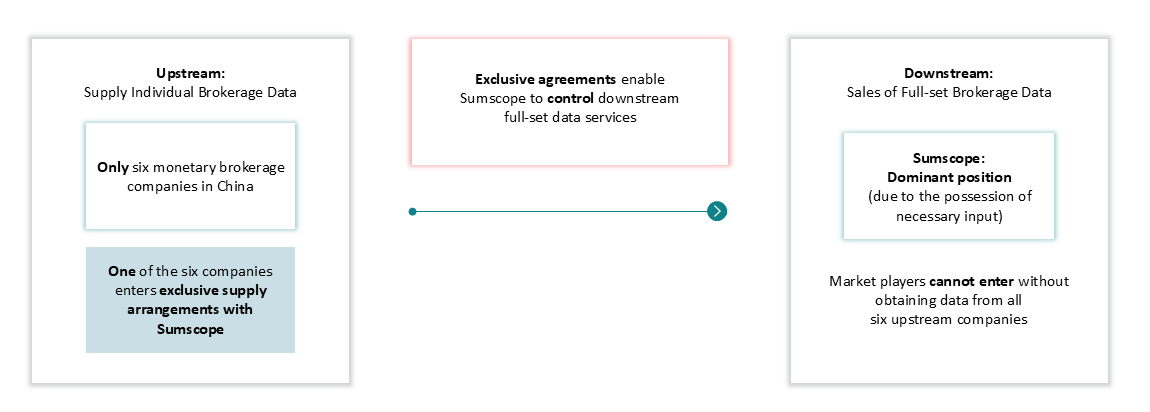

2.1 How was market dominance created?

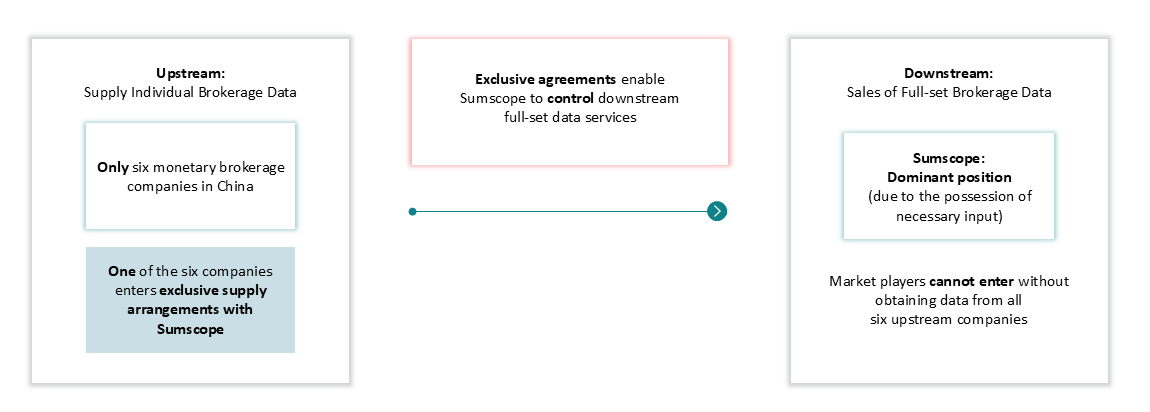

This case involved (i) upstream supply of real-time bond voice brokerage data by individual brokers (“Individual Brokerage Data”) and (ii) downstream supply of full-set data for specific bond types (“Full-set Brokerage Data”).

Sumscope gained dominance by securing exclusive access to essential upstream data, creating a bottleneck that restricted competitors’ access and allowed it to dominate the downstream market.

Figure 3: Sumscope’s market dominance

Source: Compiled from the Sumscope Case

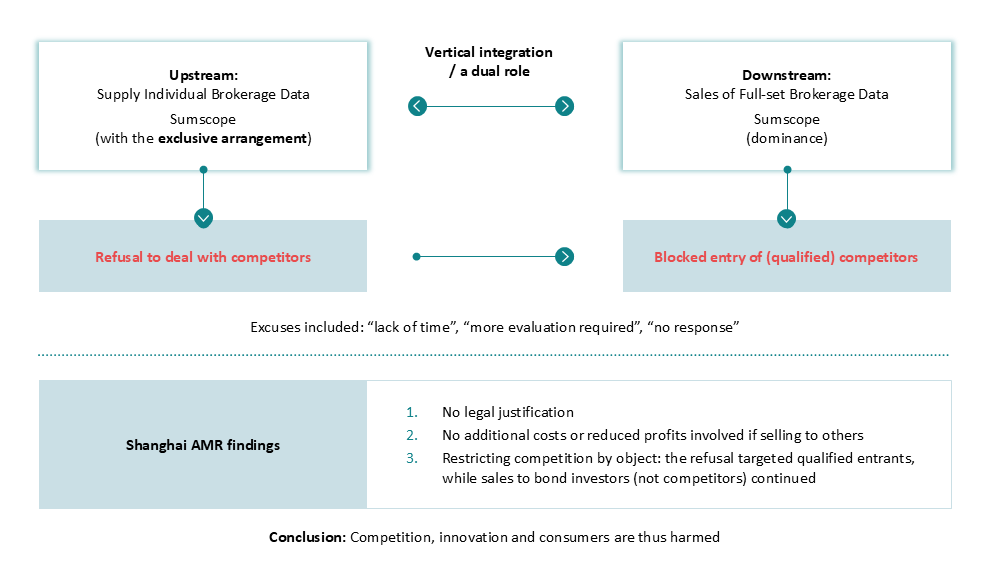

2.2 How did Shanghai Administration for Market Regulation (Shanghai AMR) determine Sumscope had abused its dominance?

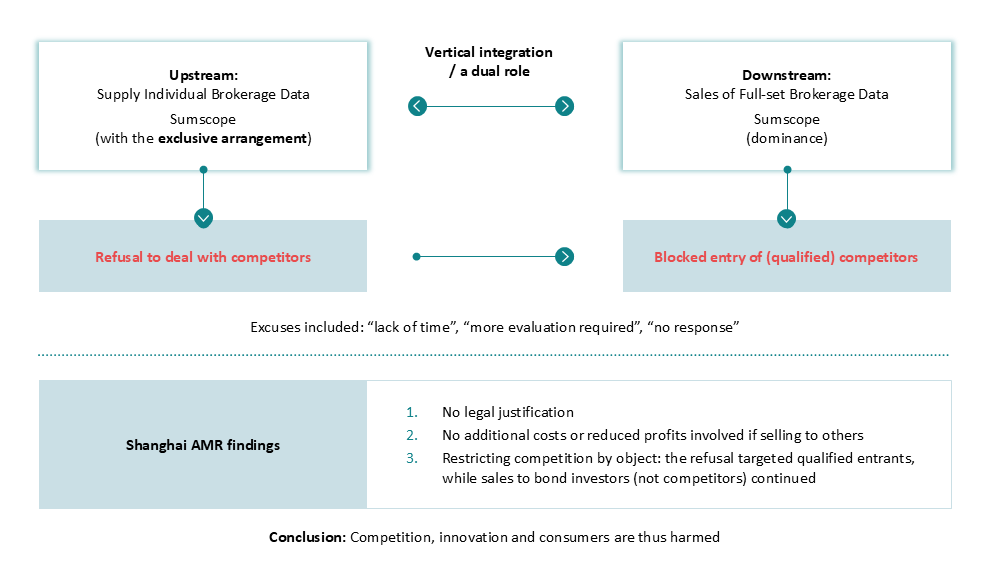

Figure 4: Refusal to supply (2019 – March 2023)

Source: Compiled from the Sumscope Case

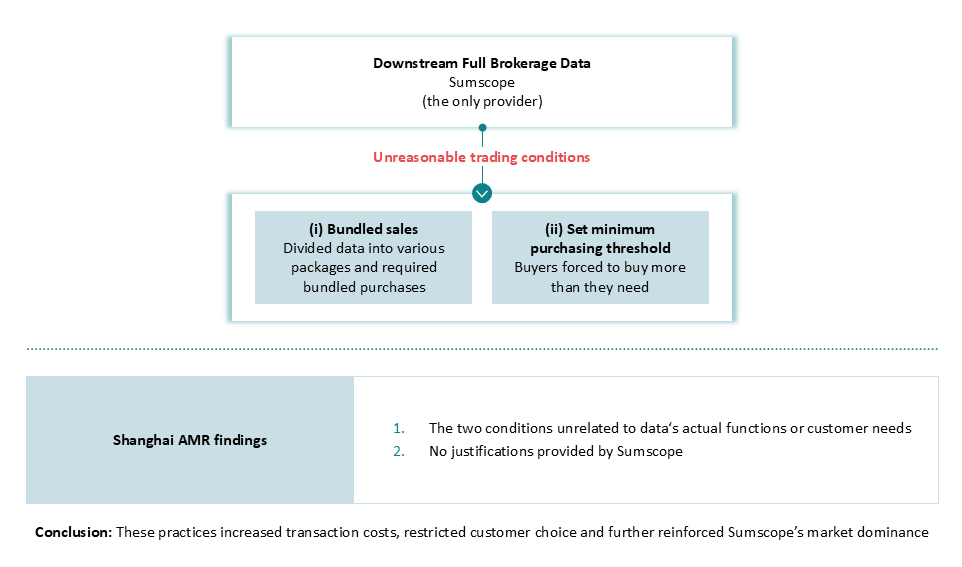

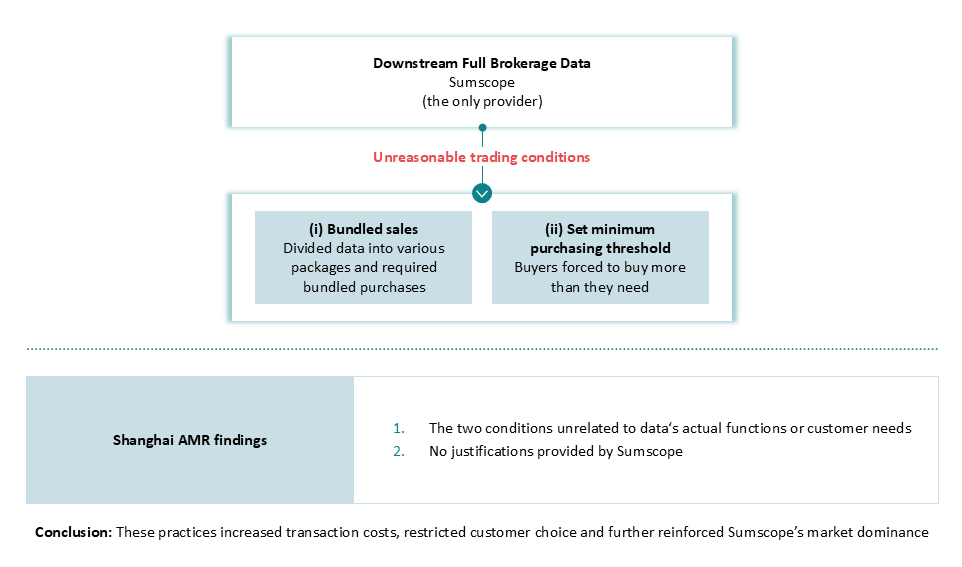

- Imposing unreasonable trading conditions

Figure 5: Imposing unreasonable trading conditions (2019 – March 2023)

Source: Compiled from the Sumscope Case

2.3 Key takeaways

- Form-based as opposed to effects-based: understanding Mainland China’s approach

Mainland China’s antitrust enforcement on abuse of dominance is more form-based, in contrast to the EU’s effects-based model. Under the Anti-Monopoly Law (AML), certain behaviours are presumed anticompetitive – suggesting a lighter burden on regulators to prove violations.

- Data becomes a critical input

Regulators are increasingly treating certain types of data as essential, non-substitutable inputs – a shift from earlier views that data is easily replicable. In Sumscope, bond voice brokerage data was found to be essential and irreplaceable due to:

-

- Data uniqueness: Real-time bond quotes and transaction information from individual brokers cannot be replaced by other sources.

- Regulatory barriers: Only a few entities in the financial sector are authorised to generate such data.

- Exclusive arrangements: Sumscope’s exclusive arrangements effectively limit competitors from accessing this essential input.

These factors led regulators to treat the data as a key market resource.

Notably, in 2024, the authorities issued a notice particularly prohibiting monetary brokers from engaging in data monopolisation or exclusive data arrangements. This move reflects heightened regulatory scrutiny of data-intensive markets.

When controlling unique data that others need to access, practices like refusal to share or engaging in exclusivity arrangements may invite regulatory scrutiny – especially in data-intensive or regulated sectors.

- Mitigating factors in penalty reduction

In setting the fine, Shanghai AMR considered Sumscope’s efforts to mitigate the impact of its conduct. Most notably, Sumscope provided substantial business and technical support to help a new competitor enter the market – a remedy more commonly seen in merger cases.

This proactive step helped restore competition and address future risks, which regulators viewed as genuine cooperation. As a result, the fine on Sumscope was reduced to 2% of its previous year’s turnover.

3. Going forward

Coming up next in the final instalment of this series (Part 6), we will examine SAMR’s increasing use of soft enforcement tools and the regulator’s latest Antitrust Guidelines for Standard Essential Patents.

Before we dive in, consider these important questions:

- What enforcement tools and strategies are SAMR increasingly using?

- Which sectors are in the antitrust spotlight in SAMR’s daily monitoring?

- What can be learned from the newly issued Antitrust Guidelines for Standard Essential Patents?

To support your understanding, we include an appendix listing abuse of dominance cases from 2024 to Q1 2025, offering practical reference points as you navigate this legal update.