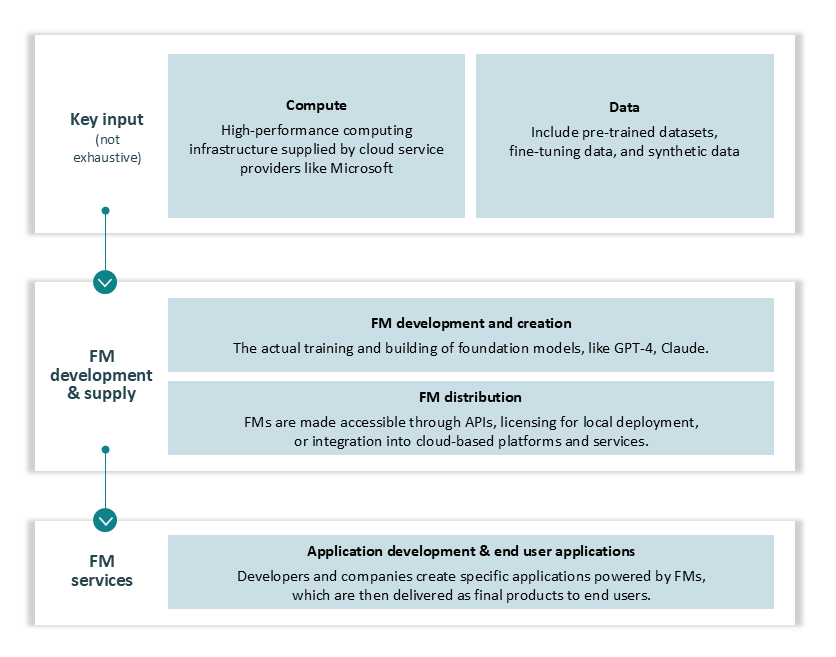

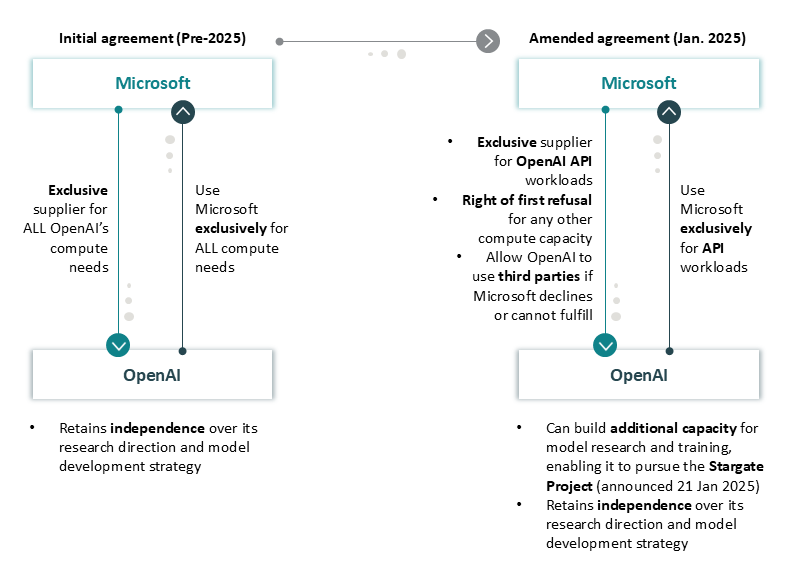

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a defining focus of the technology industry and at the heart of this wave are foundation models (“FMs”) – large-scale AI models trained on vast amounts of data (such as text, images or code) to perform a wide range of tasks, such as GPT-4 and Claude.

These models typically use advanced machine learning techniques, requiring significant computational resources to train. Access to these models is becoming crucial across industries, as they underpin a wide range of AI applications.

A key input in FM development is the access to high-performance computing resources, typically delivered through cloud infrastructure. This reliance has driven the rise of vertical integration in the AI ecosystem.

This legal update explores competition challenges arising from such AI partnerships, examining merger control issues and how strategic AI alliances are coming under the scrutiny of competition authorities.

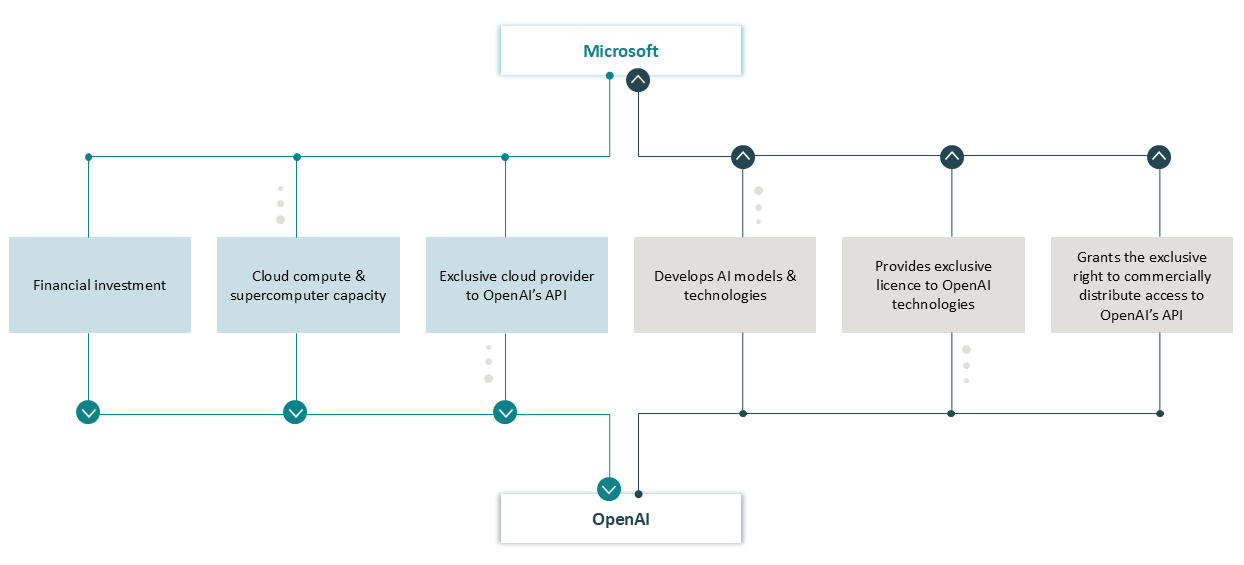

Figure 1: Overview of the supply chain of FM development

(Source: Compiled from CMA FM Report)

Vertical relationships in AI development

One prominent form of vertical integration is the formation of strategic partnerships between cloud providers and FM developers to streamline both model development and deployment. These partnerships often include investments and/or equity acquisitions in FM developers, though specific terms and structures may differ.

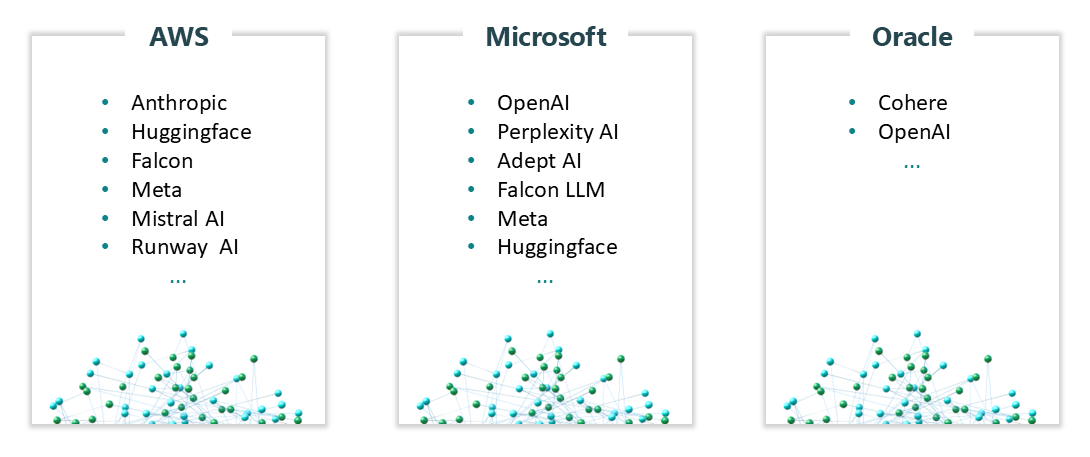

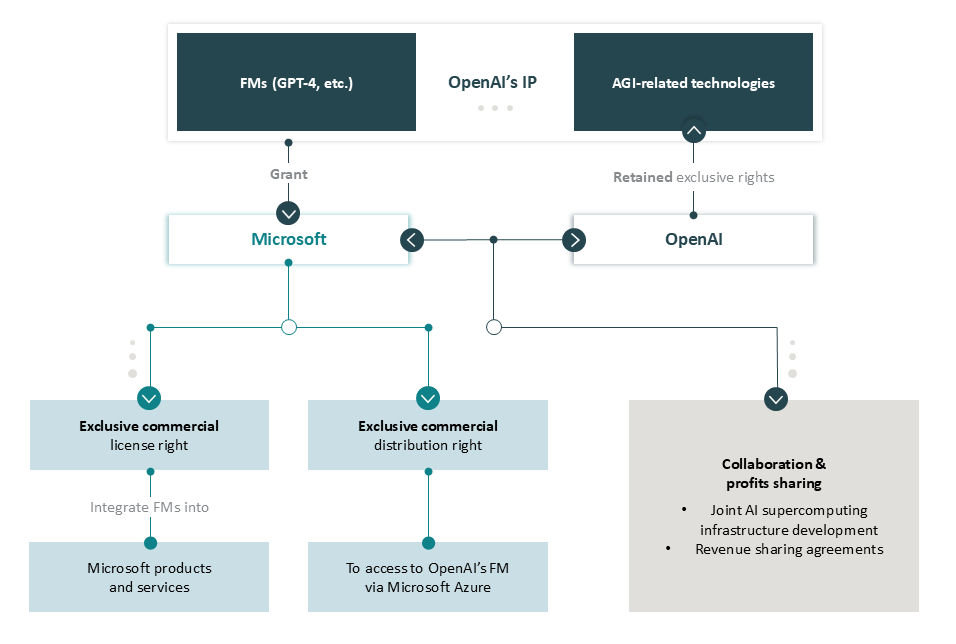

Below is a non-exhaustive list of notable partnerships between cloud providers and FM developers.

Figure 2: Exemplary partnerships between cloud providers (e.g. AWS, Microsoft) and FM developers (e.g. OpenAI, Anthropic)

(Source: CMA Cloud Infrastructure Services)

Microsoft and OpenAI partnership overview

One of the most high-profile examples of strategic partnership is between Microsoft and OpenAI, which has attracted significant regulatory attention – including investigations by the European Commission (“EC”), the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (“CMA”) and the German Bundeskartellamt.

While these authorities have concluded that the partnership does not qualify as a merger or confer control that would trigger a formal merger review, their scrutiny highlights the potential merger control concerns such alliances may raise.

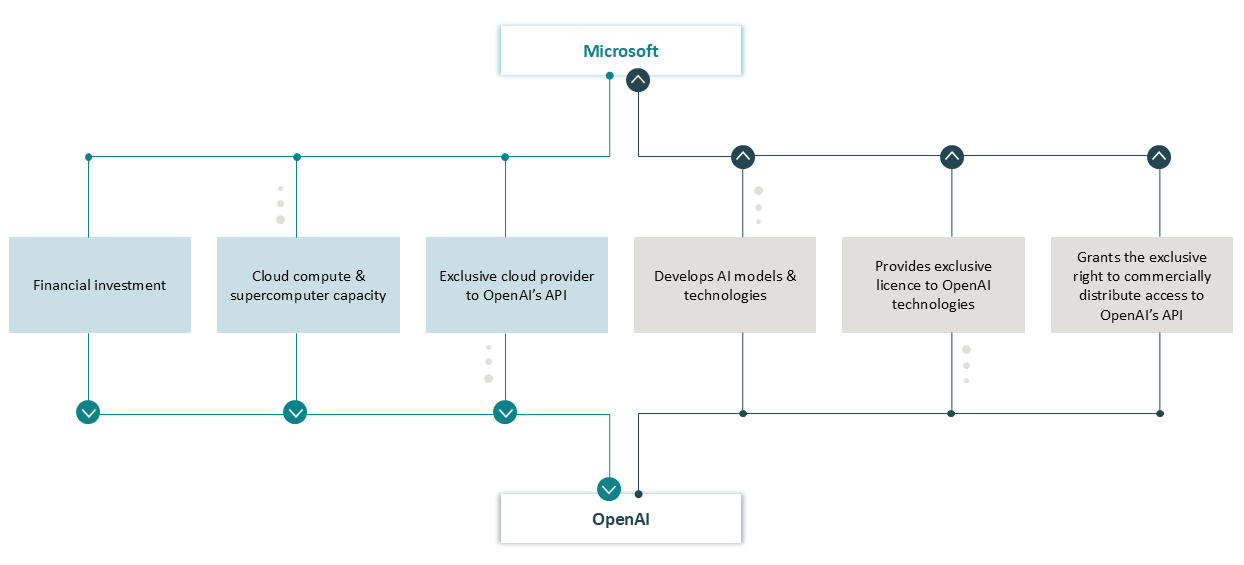

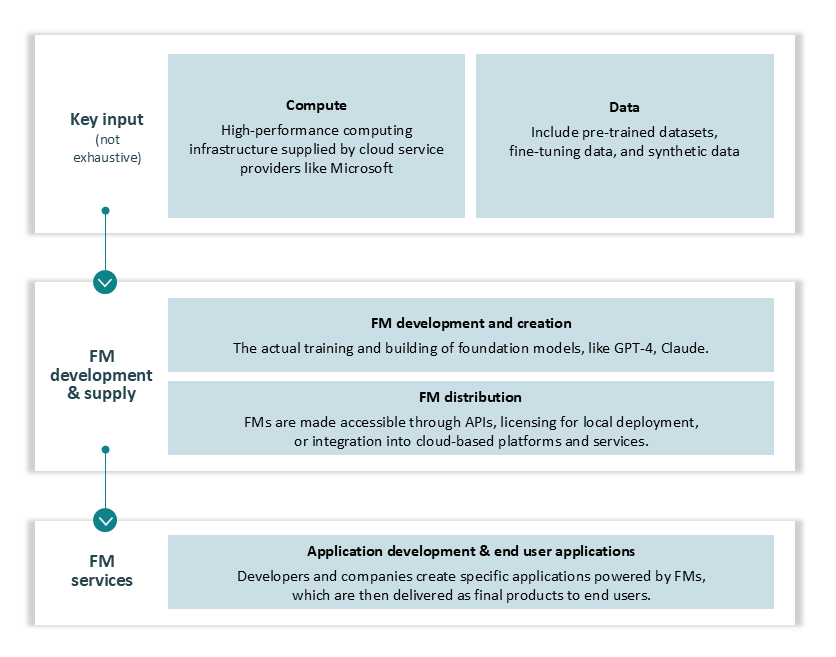

Microsoft and OpenAI first entered into this strategic partnership in 2019, with Microsoft serving as both funding investor and provider of cloud computing and supercomputing capacity. In return, OpenAI utilises Microsoft’s infrastructure to develop its FMs technologies and grants exclusive licence to commercialise these technologies, including through Azure.

Since the initial agreement, the partnership has evolved with Microsoft becoming OpenAI’s largest investor, contributing over US$13 billion between 2019 and 2024.

The diagram below illustrates the collaboration relationship between Microsoft and OpenAI.

Figure 3: Collaboration relationship under Microsoft/OpenAI partnership

(Source: Compiled from CMA Decision)

Regulatory probe into merger control issue

The Microsoft-OpenAI partnership has granted Microsoft material influence over OpenAI, as Microsoft itself acknowledges. However, merger control regulations are only triggered when there’s a change of control or acquisition of de facto control.

As the CMA notes, there is no bright line between material influence and de facto control. Assessing whether that threshold is crossed requires looking beyond formal agreements to the commercial realities of the relationship.

In December 2023, the CMA launched an investigation into whether Microsoft’s partnership with OpenAI, or any changes to it, could have resulted in an increase in Microsoft’s influence on the level of de facto control.

The CMA focused its assessment on three key areas of potential influence:

- Investment and corporate governance

- Provision of compute capacity

- Licensing and commercialisation of intellectual property

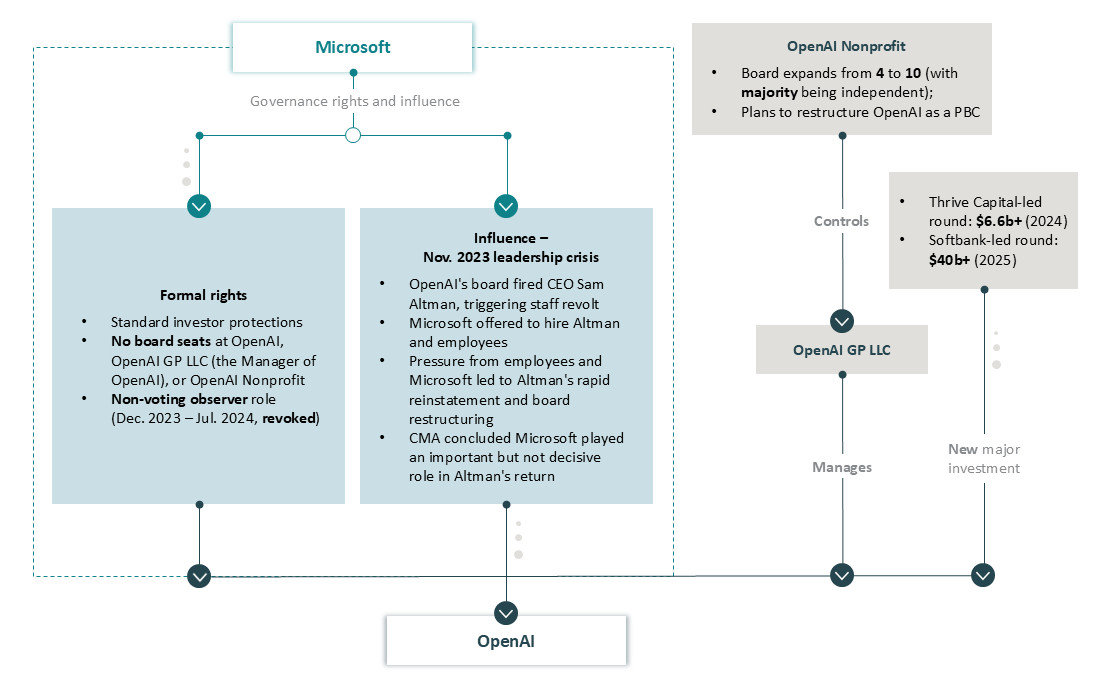

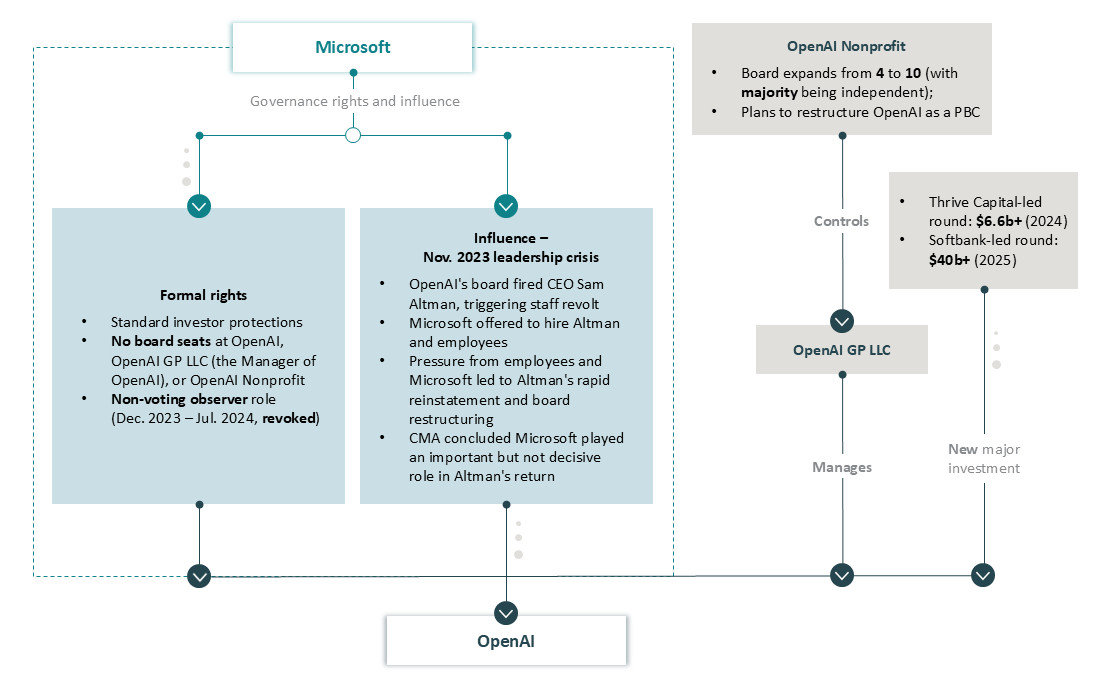

Financial investment and corporate governance

Microsoft kept limited governance rights over OpenAI – its veto rights are mainly restricted to typical financial investor protections. Microsoft does not have a right to appoint a director to either OpenAI, OpenAI GP LLC (the entity that manages OpenAI) or OpenAI Nonprofit (the entity that controls day-to-day operation of OpenAI).

While Microsoft briefly held a non-voting observer seat on the OpenAI Nonprofit board after a November 2023 leadership crisis, this seat was relinquished in July 2024.

The November 2023 crisis – when Sam Altman was dismissed briefly and quickly reinstated following staff revolt and Microsoft’s supportive intervention – highlighted Microsoft’s material influence. However, the CMA concluded that Microsoft’s influence was important, but not the decisive factor in Altman’s reinstatement.

Since then, OpenAI has demonstrated more financial independence by successfully raising over US$6.6 billion from a Thrive Capital-led investment round in October 2024, and securing another US$40 billion from a Softbank-led round in early 2025.

In December 2024, OpenAI Nonprofit announced plans to restructure as a Public Benefit Corporation (“PBC”) to attract more conventional investment. This move could further diversify OpenAI’s funding sources and reduce reliance on Microsoft, though the future size and terms of Microsoft’s stake in the PBC remain unclear.

Figure 4: Microsoft’s governance rights over OpenAI

(Source: Compiled from CMA Decision)

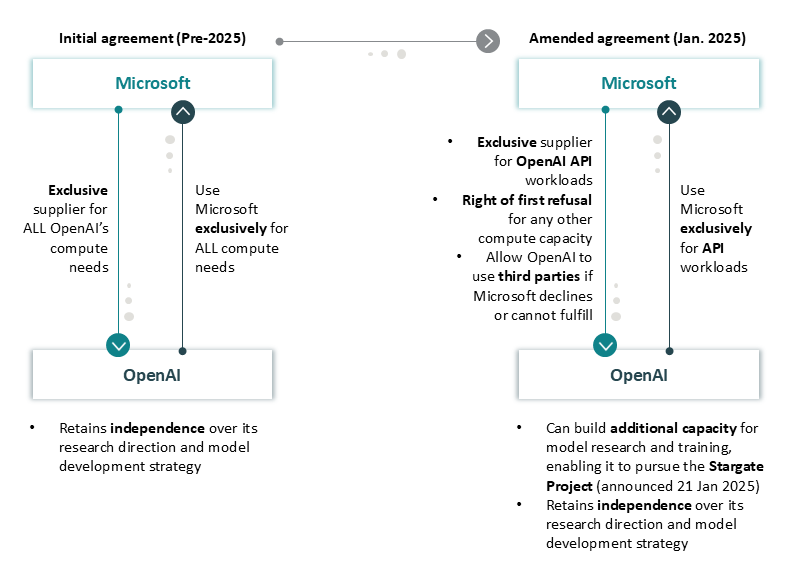

Compute capacity supply

Compute is a critical input for developing FMs and FM-based services. An agreement to supply compute – especially on an exclusive basis – could amount to acquiring material influence or control, or contribute to such a finding.

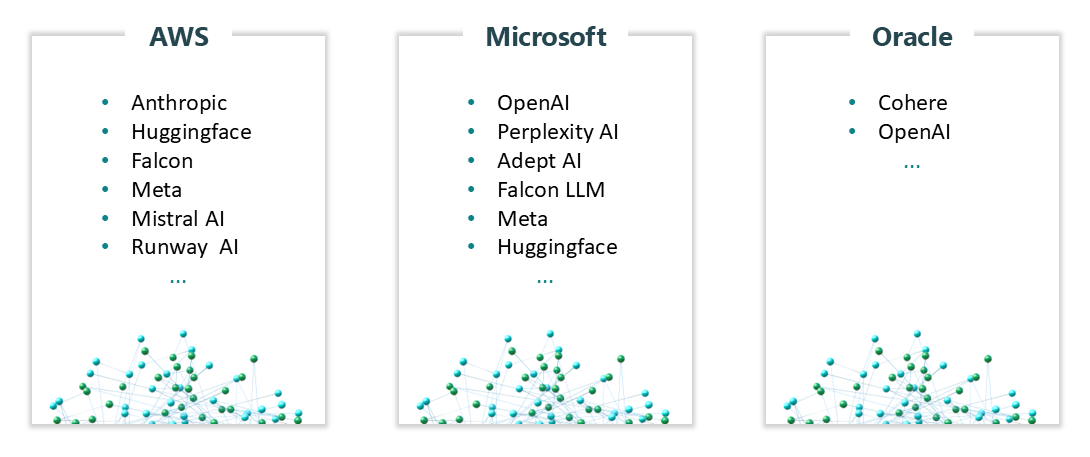

Microsoft supplies compute and supercomputer capacity to support OpenAI’s technology development. However, OpenAI determines its research direction and model development strategy independently.

Until January 2025, Microsoft served as OpenAI’s exclusive compute capacity provider for all computing needs. Following an amendment to their agreement, Microsoft now only retains exclusive rights for OpenAI API workloads, while holding a right of first refusal for any other compute capacity OpenAI may require.

Figure 5 sets out each party’s role in terms of the provision of compute capacity, highlighting how these roles changed before and after January 2025.

Figure 5: Microsoft-OpenAI’s role regarding compute capacity supply and relevant amendments

(Source: Compiled from CMA Decision)

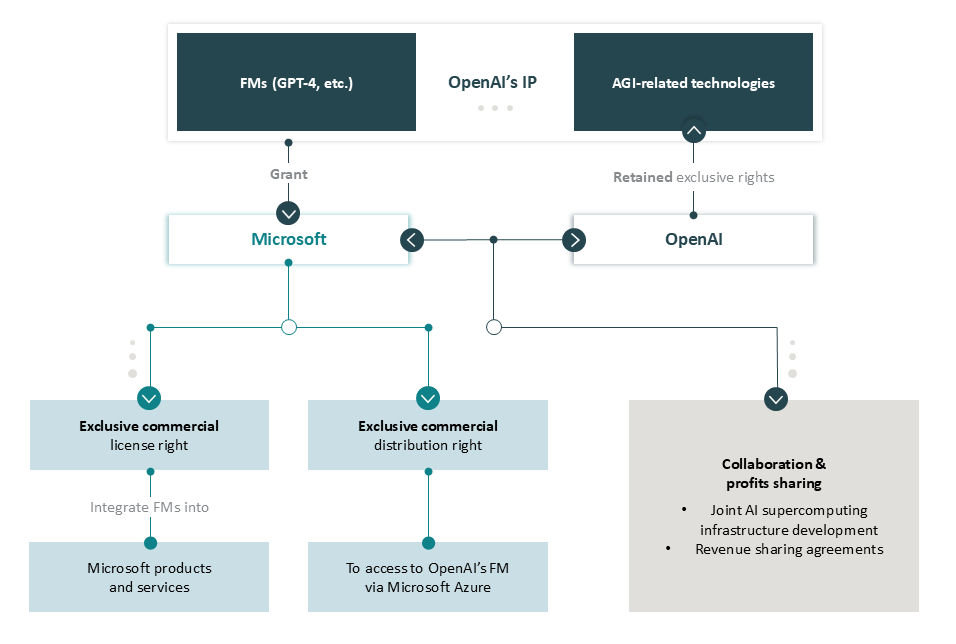

Licensing and commercialisation of IP

Microsoft holds an exclusive commercial licence to OpenAI’s FM IP, allowing it to integrate OpenAI technologies into its products and services, except for certain artificial general intelligence (“AGI”) technologies, over which OpenAI retains exclusive rights.

Microsoft is also the exclusive distributor of commercial API access to OpenAI’s models via Microsoft Azure, through the Azure OpenAI Service for customers.

The two companies closely collaborate on developing AI supercomputing infrastructure and maintain mutual revenue-sharing arrangements, both benefiting from the commercial use of OpenAI’s IP.

Figure 6: Microsoft’s IP rights and commercialisation rights under its OpenAI partnership

(Source: Compiled from CMA Decision)

Assessment on merger control issue

While Microsoft is able to exert significant influence over OpenAI, the CMA does not find this influence amount to control, nor de facto control, over OpenAI’s operations or strategic direction. OpenAI Nonprofit or OpenAI actively seek investment from additional partners to diversify funding sources.

OpenAI also retains autonomy over its research agenda and model development. Notably, following amendments to their partnership agreements in January 2025, OpenAI gained greater flexibility in sourcing compute from third parties. Microsoft’s exclusivity in compute provision was meanwhile scaled back to a first refusal right, reducing OpenAI’s operational reliance on Microsoft.

Microsoft holds exclusive rights to distribute OpenAI’s models via the Azure OpenAI Service, but OpenAI itself retains the ability to offer non-commercial API access. Crucially, OpenAI retains exclusive control over IP rights related to AGI technologies – often seen as the “crown jewels” of AI development.

As such, while Microsoft remains an influential partner, the current structure of the partnership does not support a finding that Microsoft exercises control over OpenAI. Therefore, their collaboration does not fall under CMA’s merger review scope.

Concluding implications

AI partnerships are becoming a trend in the sector, blending Big Tech’s resources with the talent and innovation of AI startups. These collaborations offer mutual benefits, but their complexity poses real challenges for traditional merger control and competition assessment.

Unlike classic mergers, these partnerships – as shown in the Microsoft/OpenAI partnership – often do not involve direct ownership or board appointments by Big Tech investors. The depth and scope of these alliances are constantly evolving, and while Big Tech investors can exert material influence, the extent of that influence remains ambiguous.

This uncertainty means there is no universal answer to whether an AI partnership will trigger merger control. Much depends not just on how the partnership is structured, but also on the jurisdiction in question.

In many jurisdictions, a transaction may be considered a notifiable concentration if it results in a change of control. Typically, “control” goes beyond simply influencing a company’s strategy — it involves owning or having rights over all or part of its assets, or holding powers that decisively affect its governance, voting, or decision-making. In contractual arrangements without direct share acquisitions, factors such as board representation or the ability to influence key financial or operational policies can be relevant to indicate control.

However, the US takes a more flexible approach under Section 7 of the Clayton Act, focusing less on strict control, and more on whether a deal could substantially lessen competition or create a monopoly. That said, even if control is not acquired, a deal that gives the acquirer or investor the ability to influence the target’s strategic or operational decisions can still fall within the scope of the Clayton Act.

This approach may become increasingly attractive to regulators as they are proactively adapting their competition framework to address the fast-evolving digital landscape. Recent developments include the EU’s consultation on revising its Merger Guidelines and the UK CMA’s taking steps to evolve its merger control scheme.

As AI partnerships are proliferating and attracting the attention of competition regulators, it is foreseeable that competition authorities may further refine their merger control frameworks to better capture such partnerships within their regulatory scope.

At the same time, competition authorities have also made it clear that this type of strategic partnership, particularly those creating vertical integration, remains firmly on their radar. Beyond merger control, these partnerships are being closely monitored by competition authorities for potential competition risks.

Given the rapid development of the sector and the proliferation of new cooperation models, there is a real opportunity for practitioners like us to help clients in navigating how competition rules may apply to their specific circumstances. Staying proactive and well-informed will be key as authorities continue to refine their approaches in response to the evolving dynamics of collaborations in the digital sector.