Part 1: Mainland China enforcement action

The pharmaceutical sector has long attracted intense scrutiny from competition regulators worldwide – and Mainland China is no exception. This was clearly underlined in March 2025 when the Shanghai Administration for Market Regulation (“Shanghai AMR”) imposed a record RMB 223.4 million in fines in a high-profile pharmaceutical cartel case (the “Decision”).

Notably, this case also sets a precedent for individual accountability: the executive responsible for orchestrating the violation was personally fined RMB 500,000, marking the first time in Mainland China that an individual was held directly liable in a monopoly agreement case.

This Decision therefore sends a strong message that Mainland Chinese competition authorities are resolute in addressing misconduct. It also offers critical lessons for businesses operating in the country’s pharmaceutical sector and beyond.

1. Key takeaways

(1) Personal liability for cartel involvement

PRC law allows fines up to RMB 1 million for individuals involved in monopoly agreements, including legal representatives, senior management, or other directly responsible persons.

The Decision highlights that liability may arise where individuals:

- Propose or instruct anti-competitive agreements

- Draft key agreement terms

- Organise meetings to exchange sensitive information

- Oversee or facilitate implementation of collusive strategies

Notably, liability is not limited to senior management – any individual with a leading and substantive role in a cartel’s formation or execution may face penalties.

(2) Ringleaders and leniency

Mainland China’s leniency policy offers strong incentives for cartel whistleblowers:

- First applicant: Up to 80% fine reduction or complete exemption

- Second: 30-50% reduction

- Third: 20-30% reduction

It marks a key distinction from Hong Kong, where ringleaders are barred from applying for a leniency marker and can only seek up to a 50% reduction through a cooperation agreement. However, Mainland China allows ringleaders to apply for leniency and receive up to an 80% discount, though full exemption is off the table.

This creates a strong incentive for companies in a leadership role of a potential cartel to come forward and cooperate with authorities. In these situations, it is essential to seek legal advice early to assess leniency opportunities and determine optimal timing for applications.

(3) Identifying cartel red flags

Companies must watch for signs of cartel activity. Red flags include: any competitor proposals or discussions about coordinating prices, discounts or fees; dividing customers or sales territories; limiting output and bid-rigging; or exchanging sensitive business information.

If approached: immediately and proactively refuse, document your rejection, and consider reporting to competition authorities.

(4) Growing focus on illegal gains confiscation

The Decision also imposed confiscation of illegal gains – an enforcement measure that was less common in past cartel cases. This reflects a stronger regulatory focus on financial recovery in antitrust enforcement.

Notably, in March 2025 the identification of methods to calculate illegal gains was listed as a legislative priority, signalling its growing importance in antitrust enforcement. This follows release of the draft Illegal Gains Identification Method by the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) in December 2021. Once implemented, it is anticipated to provide clearer guidelines for calculating illegal gains and establish a more standardised approach to quantifying antitrust violations.

What this means for businesses:

- Companies should proactively assess potential financial exposure in antitrust investigations.

- Strengthening compliance programmes is key to reducing enforcement risk.

- Importantly, illegal gains are not eligible for reduction, even if the company cooperates during the investigation.

2. Looking ahead in this series

The remainder of Part 1 delves into the landmark Shanghai AMR’s Decision, presenting a comprehensive analysis of how the cartel scheme unfolded – ultimately resulting in the substantial penalty.

Part 2 will analyse the SAMR’s latest Antitrust Guidelines for the pharmaceutical sector, released in January 2025, offering insights to help companies navigate pharmaceutical agreements.

Part 3 will examine global regulatory developments, highlighting emerging antitrust issues and approaches that may influence future enforcement trends.

This series aims to provide a comprehensive perspective on the evolving landscape of antitrust enforcement in the pharmaceutical sector, equipping businesses with the knowledge to manage risk and maintain compliance.

3. Background of case

Following an investigation initiated on 30 April 2024, the Shanghai AMR discovered that three pharmaceutical companies – Shanghai Xinyi, Henan Runhong and Chengdu Huixin (collectively, the “Parties”) – had colluded to fix prices and share markets for their sales of neostigmine methylsulfate injection (“NMI”) products in the Mainland China market.

NMI is a critical anti-cholinesterase drug mainly used in anesthesiology. The Parties are leading suppliers of these NMI products, and considered to be direct competitors in this space.

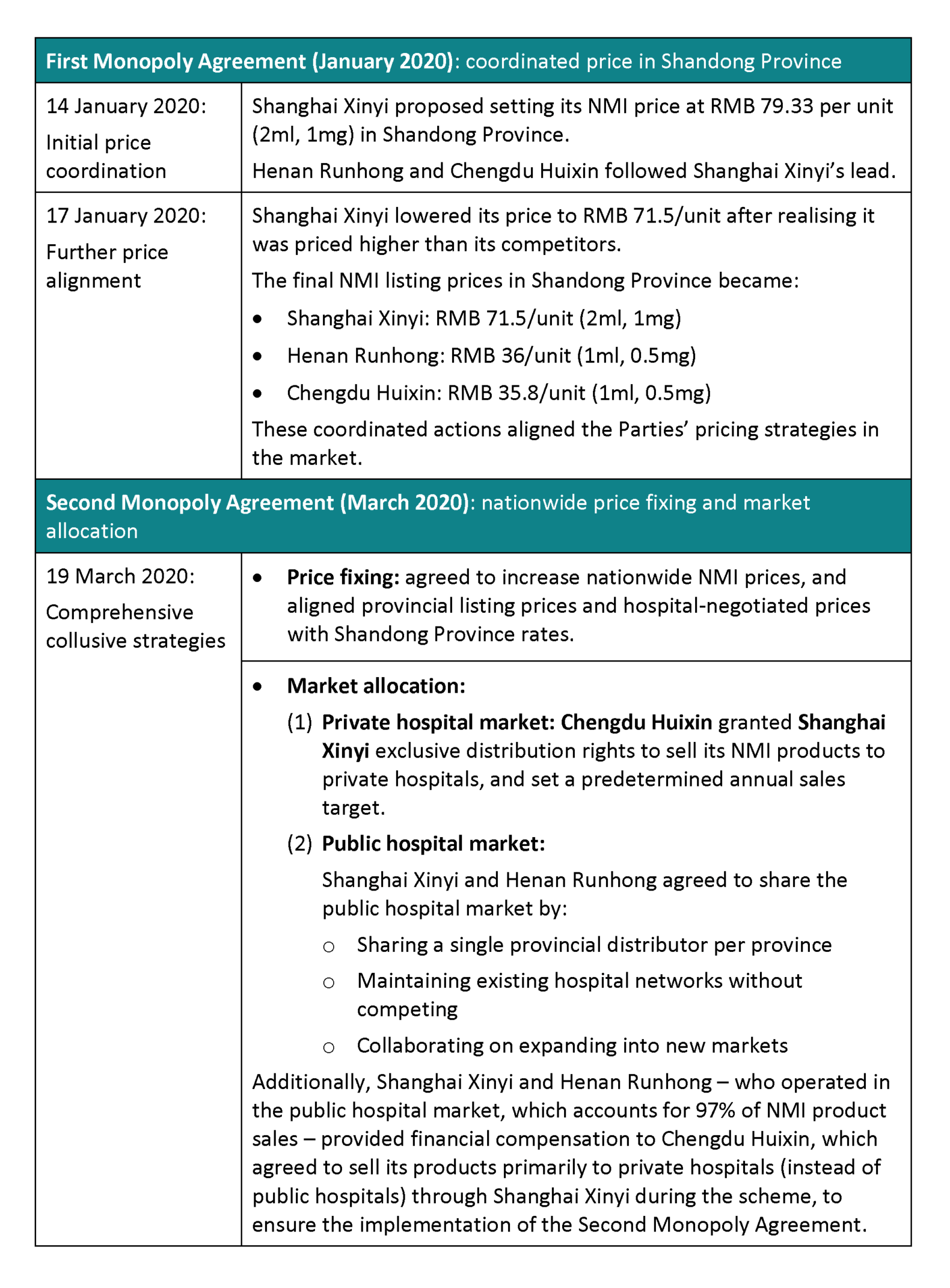

4. Two monopoly agreements

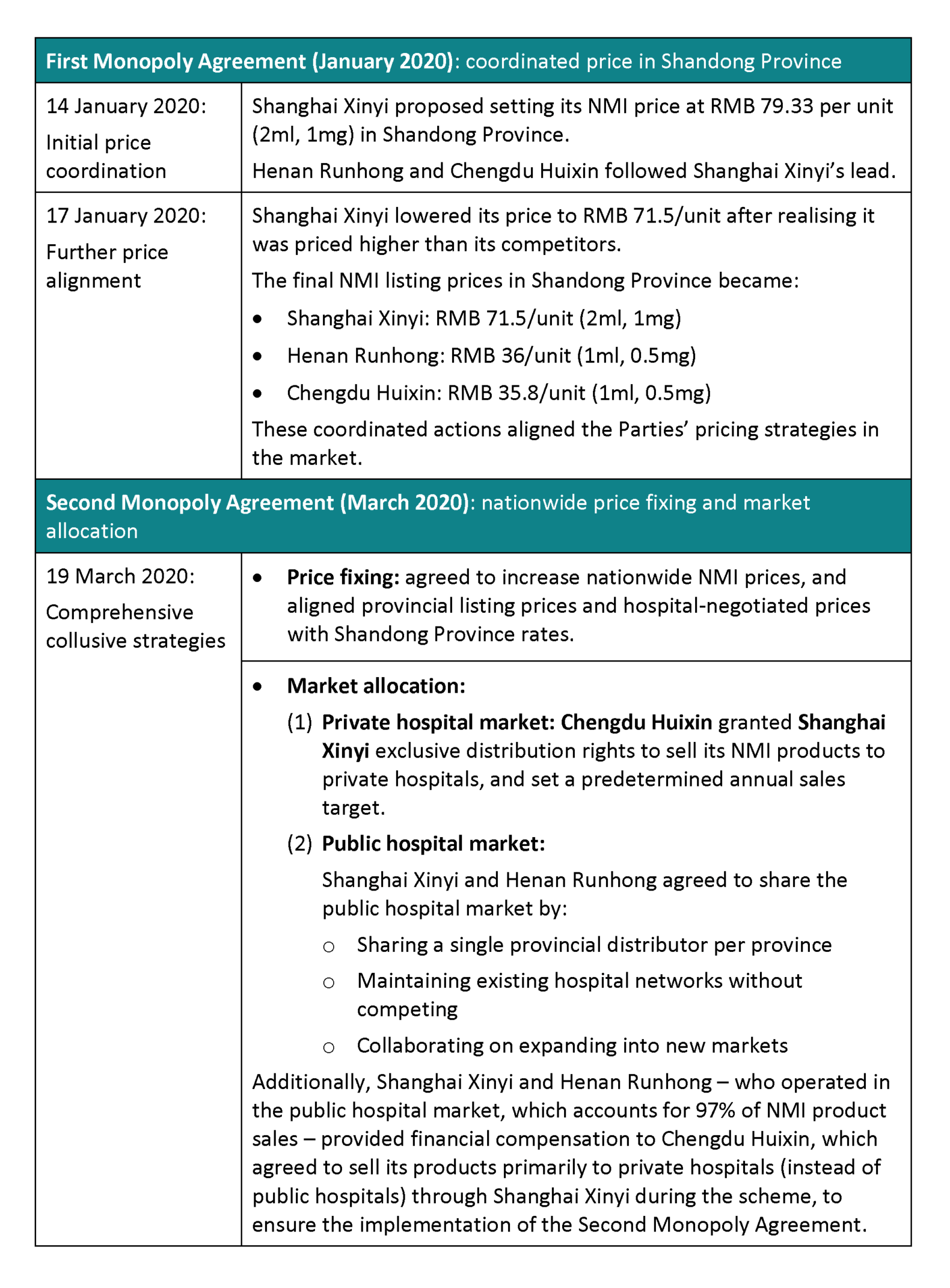

Shanghai AMR’s investigation established that two monopoly agreements (together, the “Monopoly Agreements”) operated from January 2020 to December 2023.

Table 1: Two monopoly agreements

Source: Summarised from the Decision

View the table in actual size

5. Price-fixing in Second Monopoly Agreement

Before the emergence of their agreement, the Parties had varying pricing strategies across different provinces. However, from April 2020 onwards, they began working together to systematically raise both their (1) hospital listing/negotiated price, and (2) price to delivery company for NMI.

Pricing for hospital listing/negotiated price

From May 2020 to 2022, following a series of meetings in multiple provinces, the Parties gradually raised their NMI listing prices for public hospitals.

By 2022, Shanghai Xinyi’s price had jumped from RMB 3.56-6.8 to RMB 71.5 per unit (2ml, 1mg) across 31 provinces.

Similarly, Henan Runhong and Chengdu Huixin raised their prices to RMB 36 (from RMB 1.78–5.6) and RMB 35.8 (from RMB 1.68–3.68) per unit (1ml, 0.5mg), respectively.

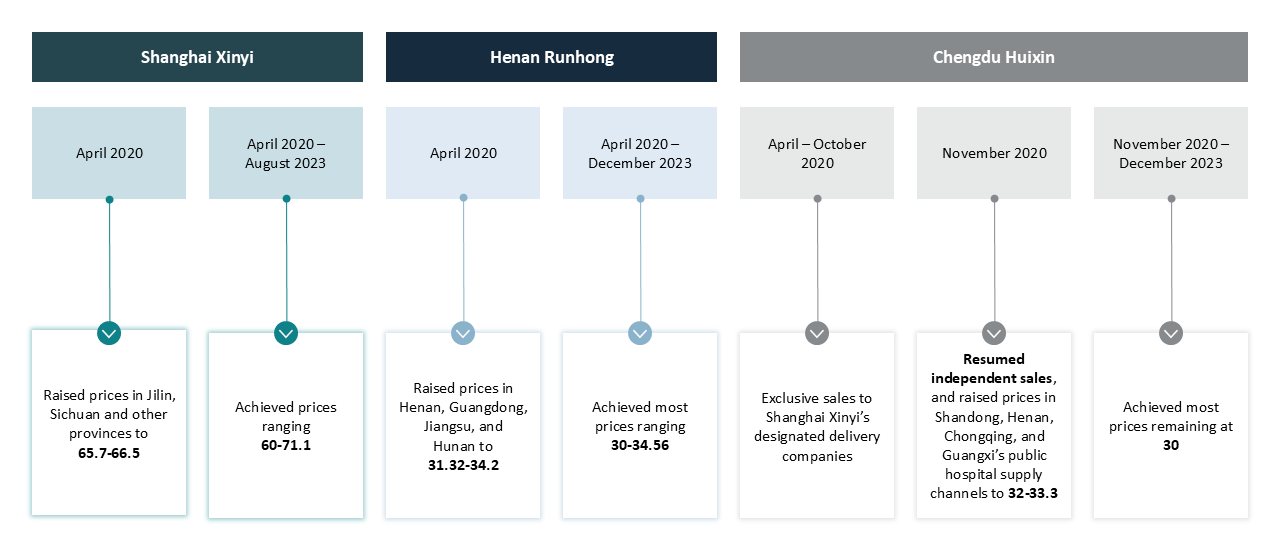

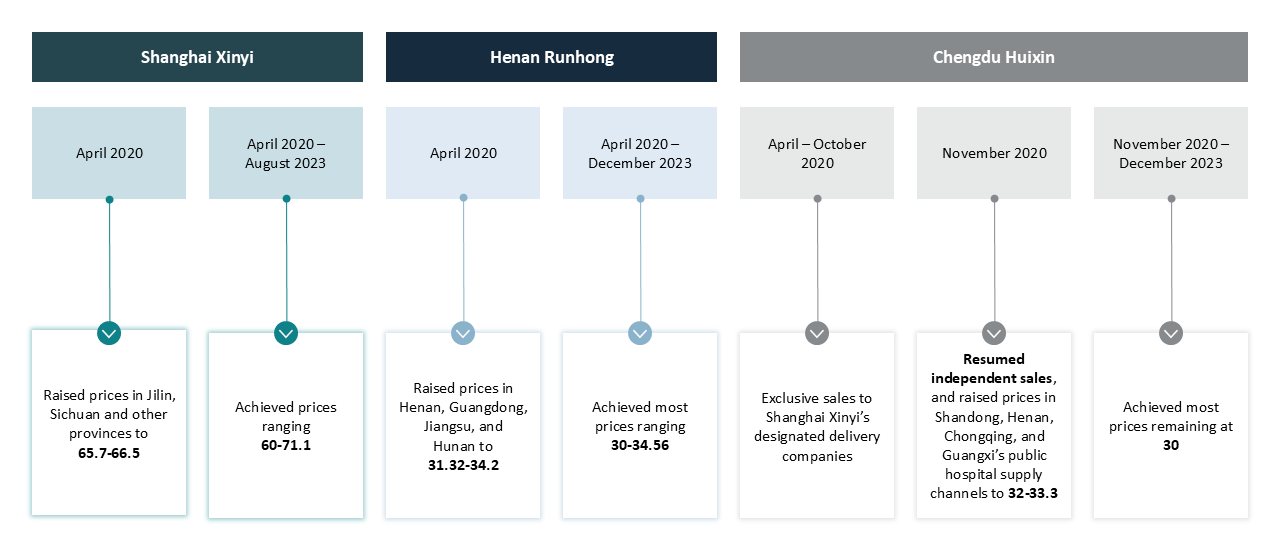

Pricing for delivery companies

The Parties steadily raised their NMI prices for delivery companies, as illustrated in Figure 1 below. By late 2023, all of them had achieved the price increase:

- Shanghai Xinyi: Raised prices to RMB 60–71.1 from RMB 3.23–6.15 per unit (2ml, 1mg).

- Henan Runhong: Raised prices to RMB 30–34.56 from RMB 1.5–5.1 per unit (1ml, 0.5mg).

- Chengdu Huixin: Raised prices to RMB 30 from RMB 1.6–3.58 per unit (1ml, 0.5mg).

Figure 1: Raising prices for delivery companies (Unit: RMB/Unit)

Source: Summarised from the Decision

6. Market allocation in Second Monopoly Agreement

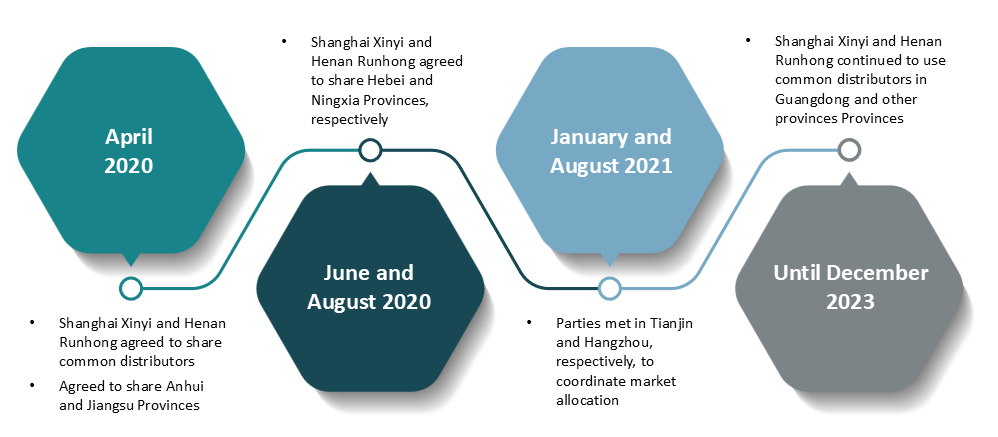

Shanghai Xinyi and Chengdu Huixin sharing private hospital market

In April 2020, Shanghai Xinyi became the exclusive distributor of Chengdu Huixin’s NMI, which prevented Chengdu Huixin from making direct sales, including to both public and private hospital channels. Instead, all distribution to private hospitals was supplied by Shanghai Xinyi.

In November 2020, Chengdu Huixin ended the exclusive agreement with Shanghai Xinyi, and resumed independent sales, but most of its products still went to private hospitals, with only a small portion able to reach public hospitals.

This arrangement significantly reduced Chengdu Huixin’s presence in the public hospital market and restricted competition in both sectors.

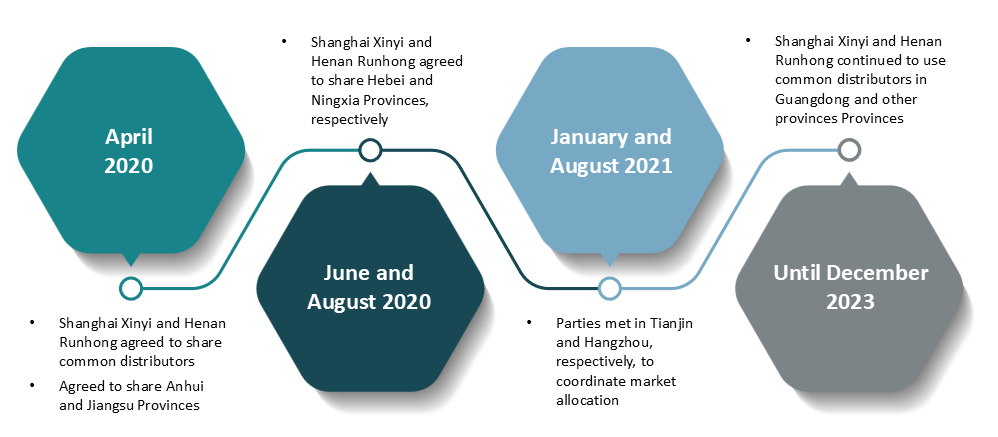

Allocating public hospital market between Shanghai Xinyi and Henan Runhong

Since April 2020, Shanghai Xinyi and Henan Runhong agreed to use the same provincial distributors to promote their NMI products. Although Henan Runhong partially deviated from this arrangement for promotion in some provinces in 2021, Shanghai Xinyi and Henan Runhong continued sharing the same provincial distributors in key regions like Guangdong Province until December 2023, helping to maintain a stable market share in public hospitals.

Figure 2: Timeline and process of Parties’ strategic market allocation

Source: Summarised from the Decision

7. Personal liability of Shanghai Xinyi GM

The general manager (“GM”) of Shanghai Xinyi’s Sales Agency Business Department played a pivotal role in executing and implementing the Monopoly Agreements, which ultimately resulted in his RMB 500,000 fine under the Decision.

How the GM drove Monopoly Agreements

- First Monopoly Agreement (January 2020)

- Instructed and facilitated the price-increasing scheme with Henan Runhong and Chengdu Huixin, and reported on the price coordination strategy at a joint meeting.

- Second Monopoly Agreement (March 2020)

- Proposed the nationwide agreement.

- Arranged compensation to Chengdu Huixin to ensure its cooperation.

- Increased Shanghai Xinyi’s listing pricing nationwide.

- Coordinated with Chengdu Huixin to share the private hospital market, and with Henan Runhong to share the public hospitals market.

- Actively worked to resolve conflicts and align the interests of the Parties.

The GM’s active role in communication, negotiation and coordination among the Parties was key to the success of the Monopoly Agreements, which consequently led to serious legal repercussions.

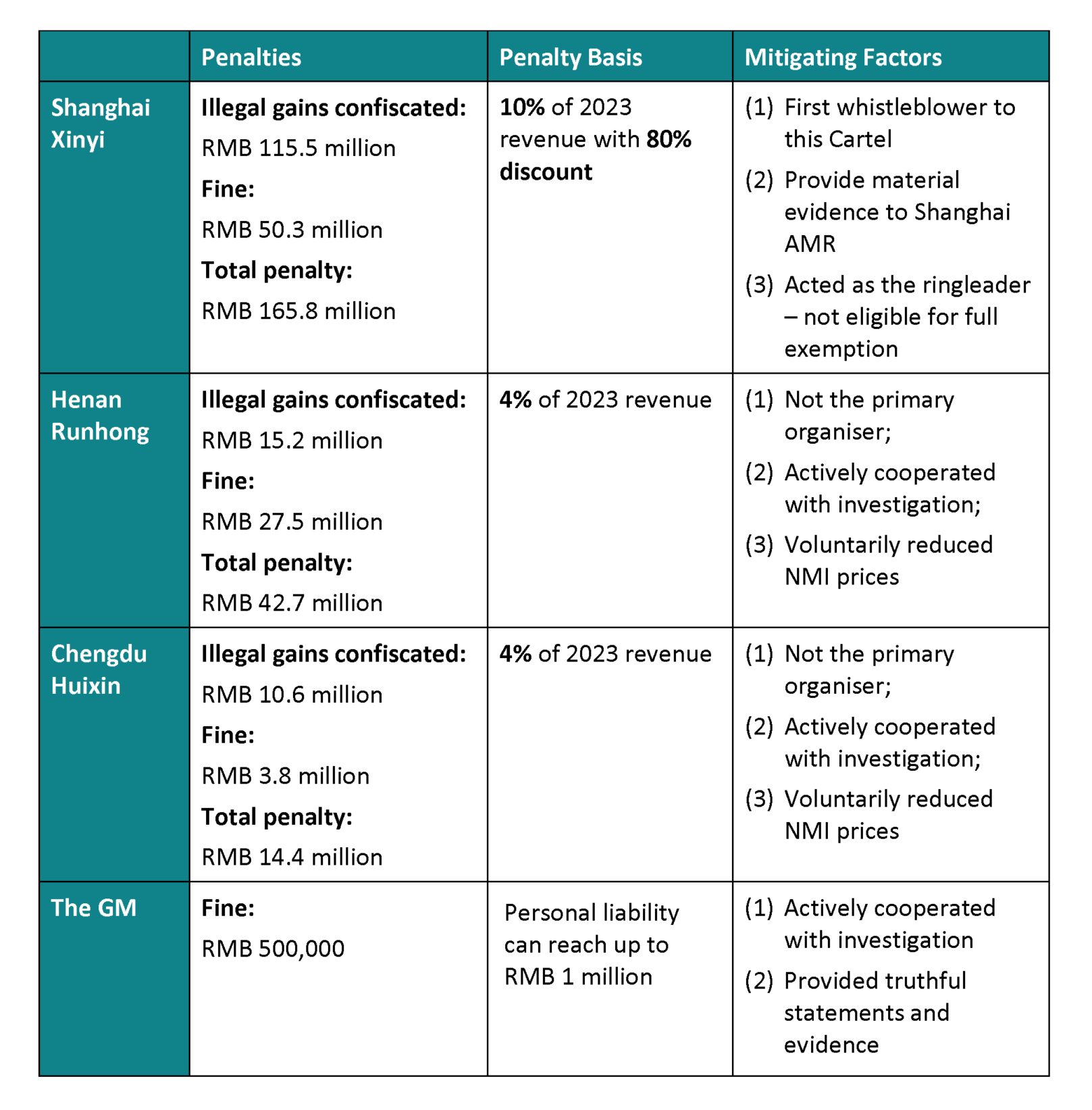

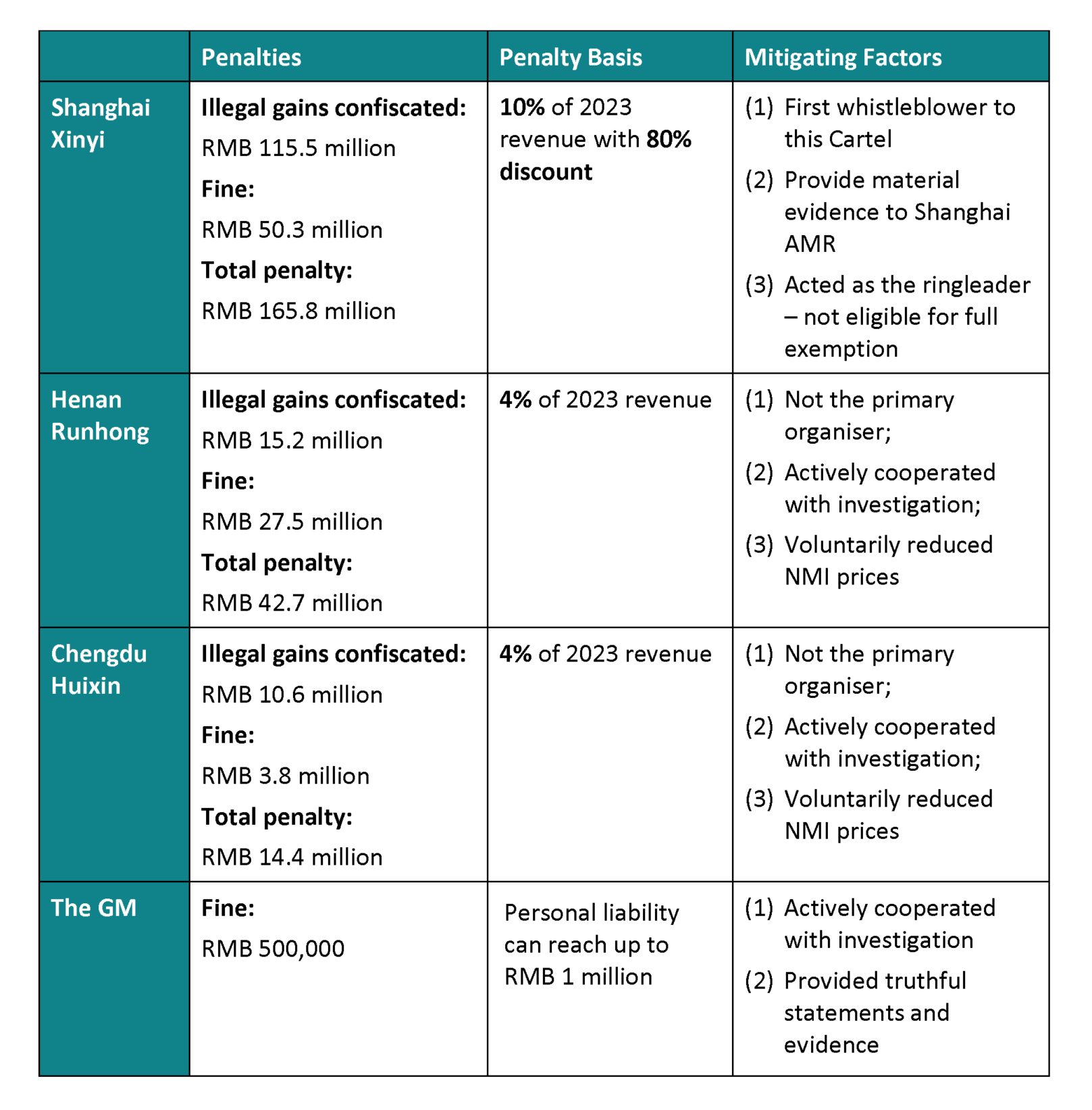

8. Penalties

The price-fixing and market allocation schemes were in this case classified as “hardcore” restrictions under Mainland China’s competition rules, resulting in direct liability. Justifying such conduct carries a high burden of proof and has a low likelihood of success.

Undertakings found liable face serious legal consequences, including orders to cease illegal conduct, confiscation of illegal gains, and fines from 1% to 10% of their previous year’s sales revenue. Directly responsible individuals may also be fined up to RMB 1 million.

This case resulted in record total fines of RMB 223.4 million. The breakdown of fines and respective mitigating elements for each party are as follows:

Table 2: Penalties and mitigating factors

Source: Summarised from the Decision

View the table in actual size

9. Going forward

This case resulted in hefty fines and severe penalties to involved undertakings and a key individual, sending a clear warning to the pharmaceutical industry – and beyond – about the serious consequences of antitrust violations.

In Part 2 of this series, we will examine the SAMR’s Antitrust Guidelines for the Pharmaceutical Sector, providing critical insights into compliance strategies and identifying potential risks in pharmaceutical agreements.

Before we dive in, let’s consider a few important questions:

- What types of conduct typically constitute a direct violation of competition rules in the pharmaceutical sector?

- Are reverse payment agreements arising from patent disputes between pharmaceutical companies always anti-competitive? What factors are considered when assessing their risk under competition laws?

- How do Mainland China’s competition regulators approach vertical restrictions in agreements (which are common in pharmaceutical agreements between suppliers and distributors)?

- What situations are generally not considered monopoly agreements in the context of the pharmaceutical sector?