Part 2: Monopoly agreements under new antitrust guidelines

Mainland China’s State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) issued the final Antitrust Guidelines for Pharmaceutical Sector (“Guidelines”) on 24 January 2025, marking a significant step in the country’s ongoing efforts to strengthen competition compliance in this vital industry. Built upon a draft released for feedback last August, the Guidelines apply to traditional Chinese medicine, chemical drugs and biological products.

Hardcore restrictions: what you need to know?

In line with Article 17(1)-(5) of the PRC Anti-Monopoly Law (AML), the Guidelines highlight five “hardcore” restrictions that are presumed to violate the AML. Overcoming this presumption is particularly difficult as parties must meet a very high burden of proof to justify any exemption.

The five “hardcore” restrictions are: price fixing, output restrictions, market division, joint boycotts and limits on new technology development.

Since the SAMR’s consolidated antitrust enforcement to Q1 2025, six cases of horizontal agreements in the pharmaceutical sector have been penalised – mainly for price fixing, output restrictions and market division.

(1) Price fixing

Price fixing is by far the most common violation. Of the six cases, five involved companies colluding to coordinate prices – commonly sales price and bidding quote – through formal agreements or meetings, and also via messaging apps or third-party intermediaries.

In some instances, like the Glacial Acetic Acid API case (2018), there was no written agreement at all; instead, companies reached a mutual understanding to fix price through communications facilitated by a third party.

The Guidelines highlight that collusion can now occur through online platforms, apps or algorithms. In response, Chinese competition authorities are increasingly leveraging AI technologies to monitor pricing trends and potential alignment in key sectors such as pharmaceuticals – sending a clear message to companies about the importance of maintaining robust compliance practices.

(2) Output restrictions

The Guidelines clearly flag limits on product quantity or type – such as production caps, sales restrictions or bans on external sales.

In past cases, indirect compensation schemes were used to hide cartel activities. To disguise the arrangement, companies were found using financial schemes such as selling products at artificially low prices and then repurchasing them at higher prices, sometimes with the help of downstream partners.

The introduction of the Two-Invoice System in 2016, which restricts distribution to a single authorised intermediary, has increased transparency and made it harder to use such compensation schemes in public hospital sales. However, risks can remain – especially in areas like private hospitals or pharmacies, where distribution chains remain more complex.

(3) Market division

Dividing either sales markets or procurement markets poses serious antitrust risks. This includes splitting customers, territories, market shares or even suppliers of raw materials and packaging.

Market sharing also represents the most common form of misconduct – seen in five out of the six cartel cases – and typically involves:

- Agreeing not to compete in certain regions or with certain customers

- Allocating sales quotas or market shares

- Using exclusive distribution agreements to carve up downstream market

In the pharmaceutical sector, limited suppliers and frequent use of tenders make the market sharing scheme more likely – sometimes through third-party distributors.

Any form of market division, whether formal or informal, direct or through intermediaries, is high-risk. The Guidelines also make it clear that facilitators can be held liable. Companies should closely review their distribution, procurement and tendering arrangements to ensure compliance.

(4) Joint boycotts

Joint boycotts – collectively refusing to supply to or purchase from a particular business – are considered a “hardcore” antitrust violation when used to exclude competitors. This includes not only direct refusals to deal, but also agreements blocking cartel participants from working with specific competitors.

Horizontal boycotts are generally presumed illegal (unless in certain research and development (R&D) collaborations that meet specific conditions), but vertical boycotts may be more justifiable – for example, jointly sourcing only from suppliers with higher environmental standards.

Although there are no recent pharmaceutical cases, a 2023 Supreme People’s Court (SPC) decision in another industry illustrates the risks. In this case, rice noodle manufacturers colluded to force intermediaries and retailers to buy exclusively from them, penalising those who sourced elsewhere. This led to the exclusion and eventual foreclosure of a competitor, and the court found this anticompetitive.

For pharmaceutical companies, the message is clear: collective actions that limit competitors’ access to the market can pose a major red flag, and should be carefully reviewed, even if they are part of broader collaborations.

(5) Limits on new technology development

The Guidelines recognise that restrictions on technology acquisition, drug development or formulation improvements are generally anti-competitive. However, in the IP-intensive pharmaceutical sector, it is not uncommon for competitors in R&D partnerships to limit independent research within agreed areas during the collaboration to focus resources and avoid duplication.

Article 18 of the Guidelines allows exemptions for R&D collaborations that expand drug variety, improve safety and efficacy, shorten development cycles, lower costs or ensure supply during public health emergencies.

That said, these restrictions must be assessed case-by-case. Limits that go beyond the agreed scope or persist after it ends may raise antitrust concerns.

Reverse payment agreements – a growing antitrust concern

(1) What are reverse payment agreements?

Reverse payment agreements occur when brand pharmaceutical companies pay generic manufacturers to delay market entry or drop patent challenges, avoiding court risk.

These arrangements raise competition concerns by eliminating (potential) generic competition, allowing patent holders to maintain high prices. Essentially, they function by sharing the market.

(2) Guidelines on reverse payment agreements

The Guidelines recognise that reverse payments between existing or potential competitors, can be anti-competitive when unjustified.

The assessment considers whether:

- Compensation significantly and unjustifiably exceeds the reasonable settlement costs.

- The agreement effectively extends the patent exclusivity or delays generic entry.

This follows the SPC’s 2021 AstraZeneca v Jiangsu Aosaikang Pharma (the “AstraZeneca Case”) ruling, which call for case-by-case analysis.

(3) SPC’s ruling in the AstraZeneca Case

The SPC clarified that reverse payments are not per se illegal. Instead, their legality depends on:

- The likelihood of the drug patent being invalidated without settlement.

- Whether the settlement unjustifiably extends the patent holder’s monopoly or delays generic entry.

The rationale behind these factors is as follows:

- Strong patents (unlikely to be invalidated): Reverse payments have minimal competitive impact since the patent holder would likely maintain exclusivity anyway

- Weak patents (likely to be invalidated): Such agreements can unfairly extend market exclusivity and delay generic competition, raising competition concerns

(4) Key takeaways

Reverse payment agreements are under heightened scrutiny in Mainland China, particularly when weak patents involved. Even if framed as legitimate settlements, they may violate the AML if they unjustifiably delays generic entry.

Pharmaceutical companies should thus:

- Carefully assess the patent strength before settling.

- Ensure payments reflect reasonable settlement costs, and not for market exclusion.

- Avoid clauses that extend beyond the patent’s legal protection or restrict generic competition more broadly than necessary.

Vertical agreements

(1) Resale price maintenance (RPM)

RPM agreements are presumed illegal under the AML and Guidelines unless the operator can prove they do not have anti-competitive effects.

- Direct RPM: setting fixed or minimum resale prices through agreements or notices.

- Indirect RPM: controlling profit margins, discounts or rebates, often enforced with deterrent mechanisms, including penalties, incentives and monitoring scheme.

To overcome the presumption, companies must demonstrate no harm to competition within or between brands, pricing or market entry – a high evidentiary burden to meet in practice.

Recent pharma enforcement highlights ongoing risk, especially for finished drug products sold through complex distribution networks. These are typically formalised in written agreements with compliance measures. Regulators are also watching for more sophisticated RPM tactics, such as algorithm-based price monitoring.

So far, past RPM cases have all involved finished products sold, rather than Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs). This reflects key differences in market dynamics:

- Finished drugs: more vulnerable to RPM because they are sold through multi-layered distribution networks, creating price volatility that manufacturers often try to control.

- APIs: typically sold in business-to-business transactions with higher market barriers and less price transparency, making them more susceptible to cartel or abuse of dominance rather than RPM.

There is currently no safe harbour for RPM, and any form – direct or indirect – can trigger antitrust liability by Q1 2025. As of 3 June 2025, SAMR is seeking public input on the possibility of introducing a high-threshold safe harbour. But for now, companies should continue to remain vigilant.

(2) Non-price vertical agreements

The final Guidelines take a softer approach to non-price vertical agreements in the pharmaceutical sector. While earlier drafts proposed rules on non-price restrictions such as where and to whom distributors could sell, exclusive territories, and requiring certain products to be sold, these provisions were removed from the final version.

This aligns with current enforcement practice – so far, there have been no cases penalising standalone non-price vertical restrictions.

However, important caveats remain: stricter scrutiny applies if these restrictions involve abuse of dominance, support price-fixing or RPM, or are clearly anti-competitive (such as blocking passive sales or cross-supply between distributors).

Situations not constituting monopoly agreements

The Guidelines clarify that pure agency agreements in the pharmaceutical sector fall outside antitrust regulation if:

- the agent does not take ownership of products,

- the agent does not bear sales risk, and

- the arrangement is not a disguised exclusive distribution or resale.

Typical examples include:

- agents selling products with prices and other key terms set by the supplier,

- pharmaceutical companies bidding or negotiating prices in centralised procurement with agents selling at agreed prices, or

- agents providing support services like importation or invoicing without bearing commercial risks.

This distinction is especially relevant in Mainland China’s centralised pharmaceutical procurement system, where government-led intermediaries organise tenders and negotiate prices but do not bear financial or supply risks and charge fixed commissions. These intermediaries are generally considered genuine agents under antitrust rules.

However, under Mainland China’s Two-Invoice System, delivery companies often assume inventory, financial and commercial risks, making them more independent and subject to antitrust scrutiny.

Companies should thus carefully evaluate their agency arrangements to ensure they meet the above-mentioned criteria and avoid unintended antitrust risks.

Going forward

The pharmaceutical sector remains a key focus for antitrust enforcement, and the Guidelines now offer clearer direction for companies to assess and manage antitrust risks in their operations.

In the next chapter, we will examine notable enforcement practices from other major jurisdictions. These cross-border perspectives will help clarify complex issues around monopoly agreements and provide practical insights for companies aiming to stay off the regulators’ radar.

As you read on, consider:

- How do major antitrust regulators approach reverse payment agreements?

- How do regulators assess R&D collaborations between pharmaceutical companies?

- When do price-related agreements raise red flags for antitrust regulators?

To support your understanding, we also include an appendix with relevant case examples for each identified risk area, offering practical reference points as you navigate these issues.

Appendix – Relevant Cases (2018 to Q1 2025)

1. Price fixing

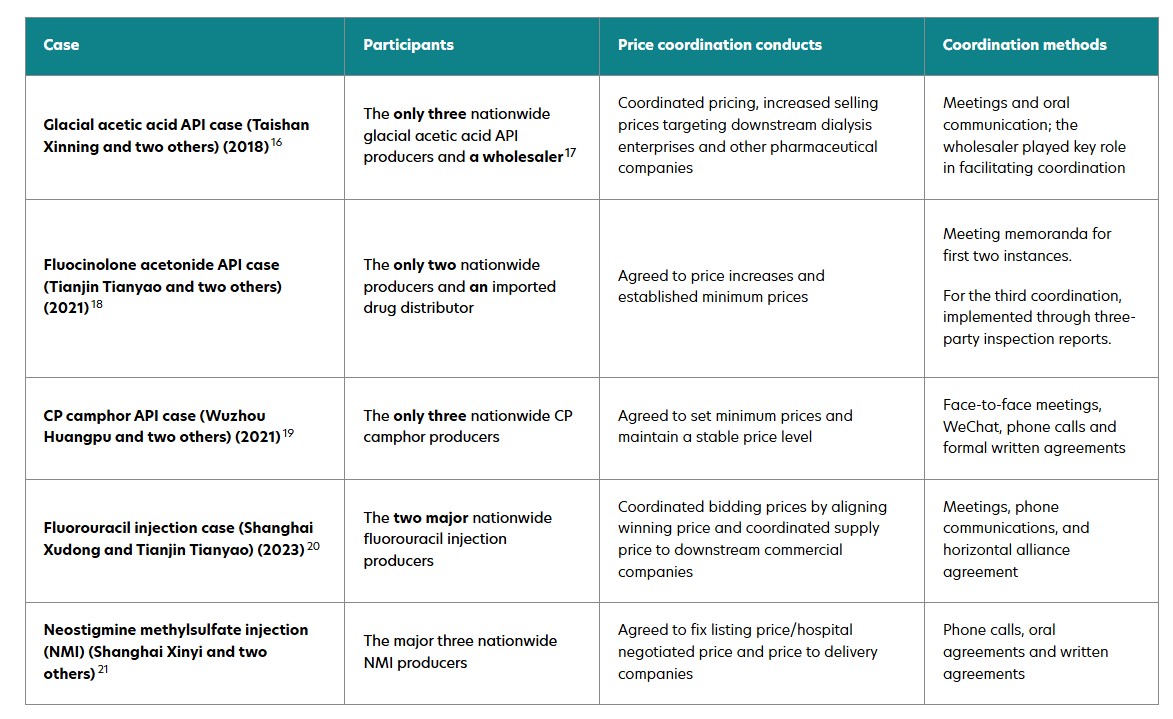

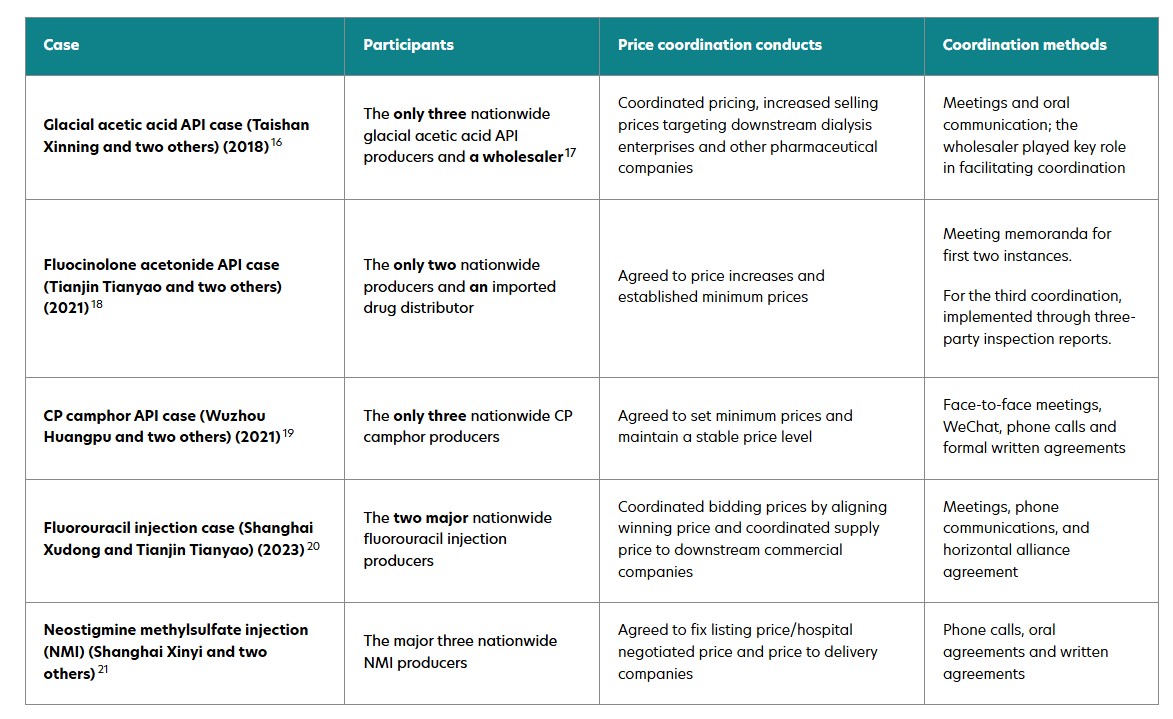

Table 1: Price fixing cases (end 2018 to Q1 2025)

Please click on the superscript numbers , , , , , for details of the corresponding remarks in the table.

View the table in actual size

2. Output restriction

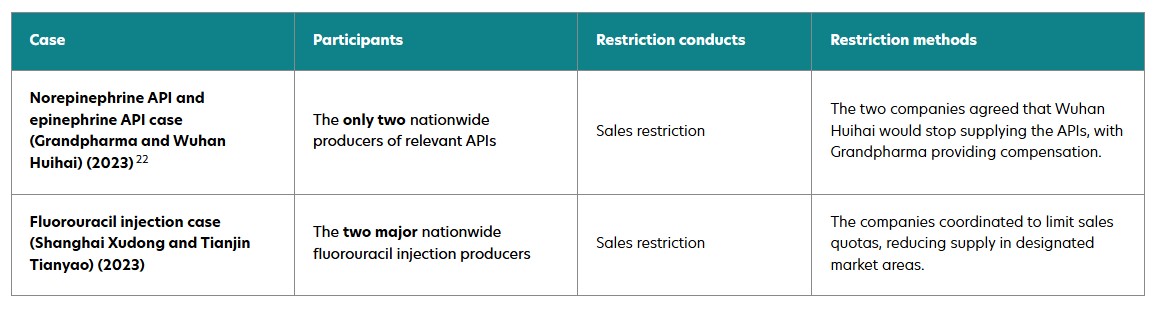

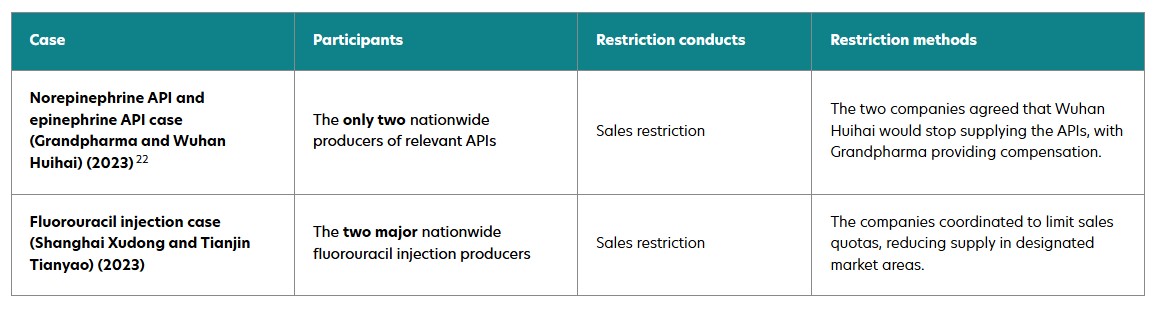

Table 2: Output restriction cases (end 2018 to Q1 2025)

Please click on the superscript number for details of the corresponding remark in the table.

View the table in actual size

3. Market division

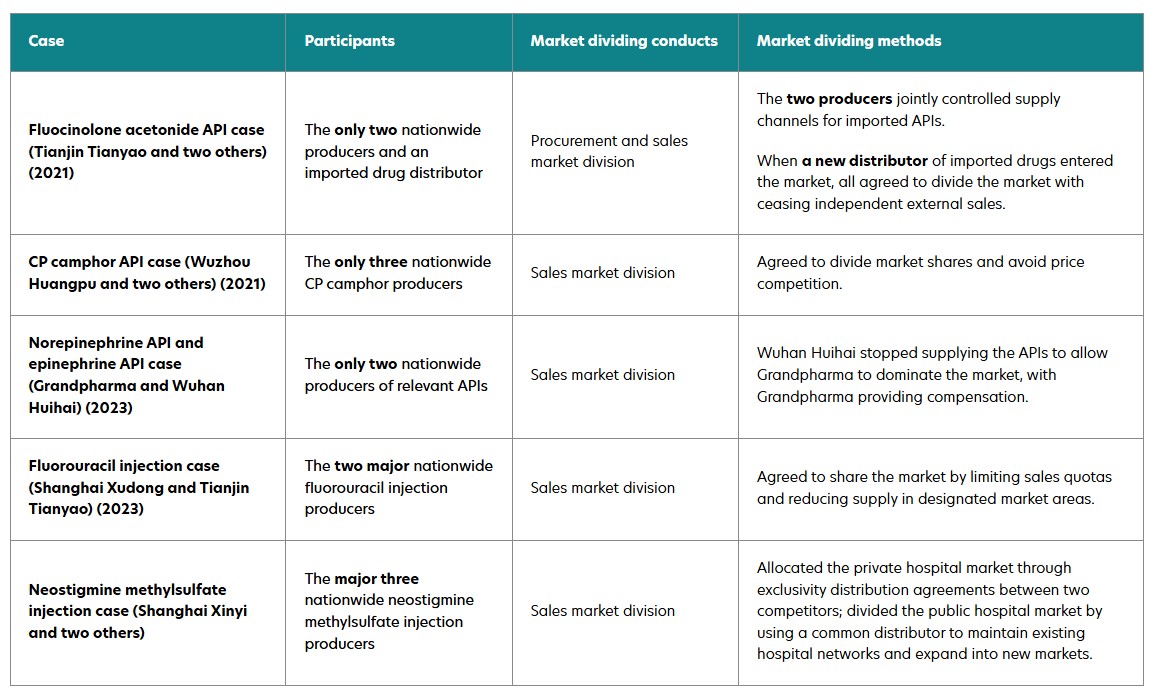

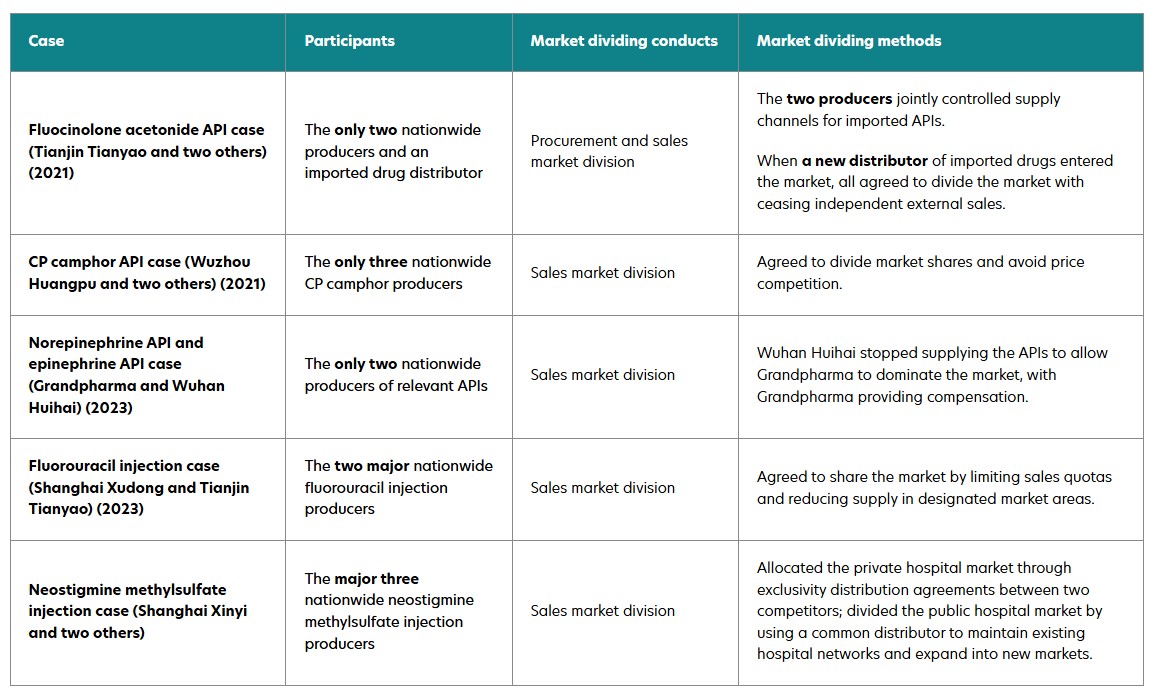

Table 3: Market division cases (end 2018 to Q1 2025)

View the table in actual size

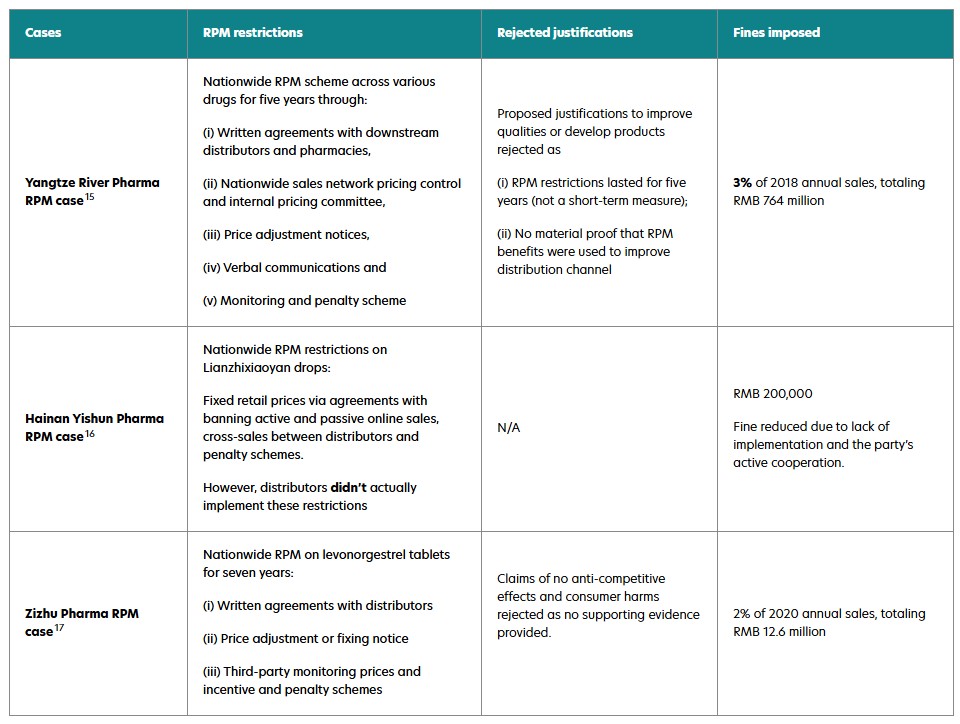

4. RPM practices

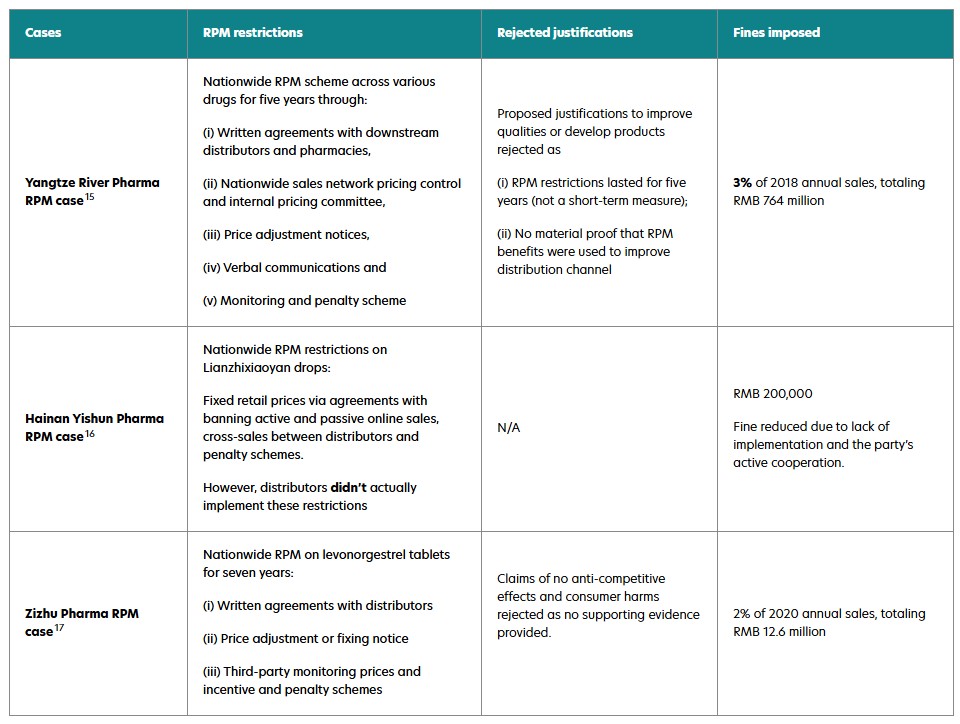

Table 4: RPM cases (2018 to Q1 2025)

Please click on the superscript numbers , , for details of the corresponding remarks in the table.

View the table in actual size