Part 2: Guidelines for Horizontal Merger Review (the “Guidelines”)

1. Highlights of the Guidelines

The long-awaited Guidelines released in December 2024 reflect the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR)’s enforcement experience and carry practical implications for companies. Businesses must now proactively consider how these changes will directly impact their strategies and due diligence processes. Key highlights include:

1.1 Market definition

Consider differentiated markets

Companies need to broaden their competitive analysis beyond direct substitutes. When assessing an acquisition, this means considering not only identical products, but also those that compete on use, design or technical features.

For example, if an originator acquires a generic drug company, the generic may still be a competitor due to its similar medical use – making the deal a potential removal of competition.

This broader assessment helps anticipate how regulators might define the market and flag competition concerns, even in niche segments.

Consider customer group discrimination

If you or the target employs differentiated pricing or conditions for distinct customer groups – such as varying prices for new rather than existing customers, or different service levels for enterprises than small business clients – you should prepare to address these distinctions.

Regulators may now define narrower markets if they detect sustained, non-cost-based discrimination with limited customer switching, potentially leading to findings of higher market power and targeted remedies, such as imposing fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (“FRAND”) terms for affected groups.

Detailed review of customer data and sales practices is key to identifying and managing these risks early.

The EU framework offers practical guidance in this scenario, emphasising on clear identification of customer groups, limited arbitrage and sustained pricing differences. These benchmarks can help companies navigate similar issues under Chinese review.

Supply chain considerations

For deals in strategic or geopolitically sensitive sectors, companies must now consider “supply chain stability” and “accessibility to key products”, going beyond traditional substitutability tests.

For example, if your merger involves a critical component supplier, you should be prepared to show it will not disrupt supply to downstream Chinese customers, even if there are alternative suppliers globally.

Consider engaging early with stakeholders and offering proactive remedies – such as FRAND supply commitments – to address potential concerns about stable supply, especially for inputs critical to China’s industrial or security interests.

Flexibility in market definition

SAMR may leave the market definition open – similar to the EU – particularly in complex or fast-evolving sectors where it is difficult to draw clear boundaries.

This means instead of trying to narrow down to a single market definition, SAMR may evaluate a range of plausible relevant markets to thoroughly assess competitive effects.

This approach is particularly relevant for businesses operating in rapidly evolving digital markets, dealing with highly differentiated products or in markets with elastic or shifting supply substitutability. Ultimately, the focus will be on the overall impact of the deal on competition, so your analysis should be prepared to address multiple market scenarios.

1.2 Market competition effects

The updated Chinese merger control guidelines introduce a clear framework for assessing competitive effects based on market concentration, providing a more predictable landscape for companies.

Presumption of market concentration degree

A structured framework using market share thresholds and the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (“HHI”) is introduced to help assess the potential competitive effects of a transaction.

Table 1: Market share threshold and corresponding level of competition concern

| Market share Threshold |

Competitive assessment |

Review approach |

| 50% and above |

Presumption anti-competitive |

Parties must rebut presumption of harm |

| 35% – 50% |

Significant scrutiny |

High risk of restrictive effects |

| 25% – 35% |

Heightened scrutiny |

Full competitive analysis required |

| 15% – 25% |

Moderate concern |

Generally not presumed as anti-competitive but requires case-by-case review for potential unilateral or coordinated effects |

| Below 15% |

Low concern |

Presumed as not anti-competitive; eligible for simplified review procedure |

Source: the Guidelines

The Guidelines also offer the HHI as a key metric for assessing market concentration post-merger. SAMR’s approach to HHI is broadly consistent with the US Merger Guidelines, showing a more stringent assessment.

Table 2: HHI Index and corresponding level of market concentration

| Market concentration |

HHI parameters |

Competitive assessment |

| Low concentration level |

Post-merger HHI <1000 or ΔHHI (delta) < 100 |

Typically unlikely to raise competition concerns |

| Moderate concentration level |

If post-merger HHI between 1000 and 1800, and ΔHHI (delta)> 100 |

May raise concerns; warrants detailed review |

| High concentration level |

If post-merger HHI >1800 and ΔHHI (delta) between 100 and 200 |

Greater risk of competition harm and subject to full review |

| Presumed harmful |

If post-merger HHI >1800 and ΔHHI (delta)>200 |

Presumes to harm competition; merging parties must rebut the presumption |

Source: the Guidelines

Emphasis on potential competition

The Guidelines put greater emphasis on potential competition – meaning SAMR may intervene even if the target is not a direct competitor today but could become one tomorrow. This is especially important in fast-moving or innovative sectors.

I. When it matters

The concern may arise when:

- the target is a rising player in the buyer’s core market with strong market power,

- the target complements the buyer’s portfolio or operates in an adjacent market that the buyer plans to enter.

These scenarios often associate with “killer acquisition” concerns – where a dominant player acquires an emerging threat to avoid future rivalry. These cases typically involve a forward-looking, and speculative assessment, with focus on:

- the target’s potential to grow: what is their technology, team, funding and strategy?

- the probability of the buyer to enter the target’s market: are there any plans, resources, incentives?

II. What evidence matters most?

To counter potential competition concerns, objective and credible evidence are essential. Regulators need to substantiate the potential competition concerns by demonstrating that the target poses a real future constraint or that the buyer is likely to become a competitor. To establish this theory of harm:

- Internal documents are key evidence: show whether the merging parties regard each other as close competitors, and whether the target has concrete plans to enter the buyer’s market actively.

International cases illustrate how this can play out in practice:

- Meta/Within (US): The Federal Trade Commission (FTC)’s challenge failed because the court found it relied on speculative arguments about Meta’s future entry into the fitness app market without substantial supporting evidence.

- A major design software merger (UK): The UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) found that the transaction would eliminate future competition, citing internal documents and business decisions made shortly before the deal – such as discontinuing overlapping products – as key evidence.

These contrasting outcomes highlight a key lesson: for potential competition concerns to hold, regulators need concrete proof—not just theoretical possibilities. Companies should be proactive in identifying and preparing relevant evidence early in the deal process.

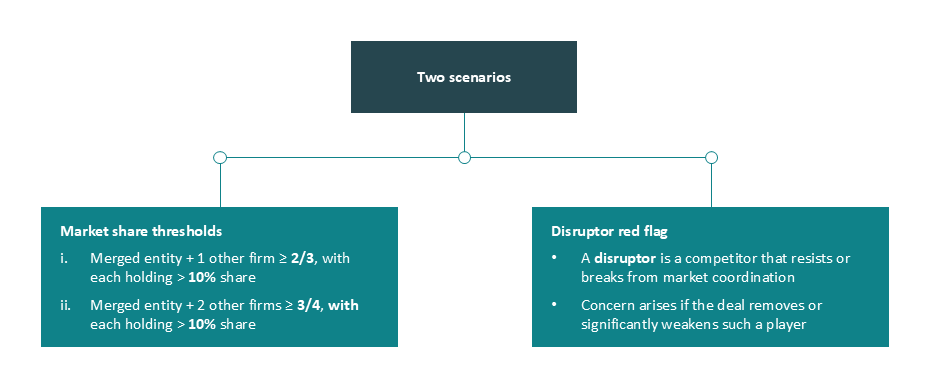

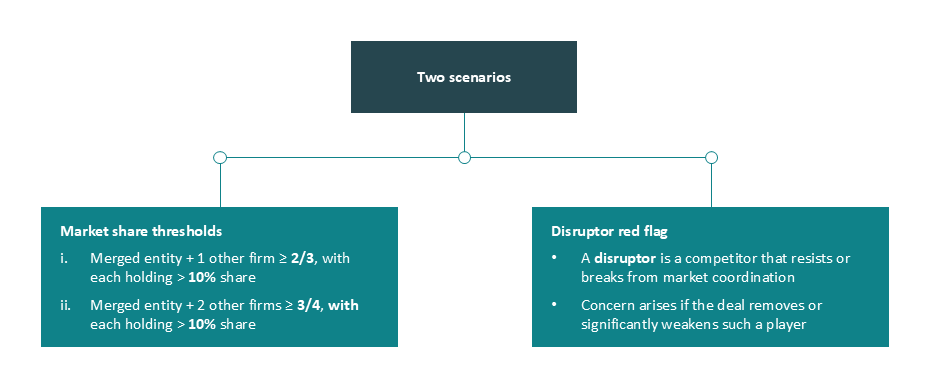

Heightened scrutiny over coordinated effects

SAMR will look for situations where the merger could lead to or strengthen tacit collusion, where companies align their behaviours without explicit or implicit agreements, hard to challenge under cartel rules. The Guidelines setout scenarios where such risks will trigger SAMR’s radar in this regard:

Figure 1: When coordination concerns arise

Source: the Guidelines

1.3 Impacts of global regulatory trend

Foreign subsidies

The Guidelines introduce foreign subsidies as a new consideration in merger control, but SAMR’s approach differs from other major jurisdictions. Companies need to be aware of how foreign government support could potentially impact SAMR’s merger review.

How SAMR’s framework works

- No automatic disclosures: Unlike the EU or US, SAMR may only investigate foreign subsidies and require such information where there is specific evidence suggesting that foreign subsidies can distort market competition.

- Sources of scrutiny: This evidence is likely to surface from:

- Complaints: Competitors or other stakeholders might raise concerns.

- Public reports: Media or other public information could highlight the receipt of foreign subsidies.

- Foreign investigations: If the deal has already been investigated by other regulators for receiving foreign subsidies, SAMR is more likely to take a closer look.

- Case-by-case approach: the Guidelines do not specify the extent of disclosure required, suggesting foreign subsidy reviews might not be a primary focus in most of merger control reviews, unless specific anti-competitive effects are evident.

Takeaways

While not mandatory for all filings, it is wise to be prepared. Companies receiving significant foreign subsidies, especially those already under scrutiny elsewhere, should:

- Assess potential impact: consider how subsidies might affect your market position or market competition in China.

- Gather information proactively: have clear information on foreign subsidies readily available to respond swiftly if SAMR requests it.

- Monitor competitive landscape: pay attention to relevant complaints or public reports to address potential issues before they become formal inquiries.

2. Going forward

Coming next in Part 3, we will explore China’s first court ruling on an appeal against a conditional merger approval, offering insights drawn from the judgment. Key questions to be discussed include:

- How can a party establish standing to challenge a merger decision by China’s competition regulator?

- What is the court’s view on problematic deals?

- What takeaways can be drawn for a deal party seeking to challenge an administrative decision by China’s competition regulator?